A quick browsing of the internet using the search “What is a Scientific Theory” will quickly find responses such as these:

A scientific theory is a principle formed to explain things that have already been shown in data.

A scientific theory often uses well-substantiated observations, principles, or facts.

Scientific theories are reasonable expectations based on observations and prior knowledge and factual information.

Scientific theories are testable which leads to the theory’s strength, validity, or invalidity.

The 2023 publication by the World Health Organization titled Low Back Pain points out these key facts (1):

- In 2020, low back pain (LBP) affected 619 million people globally and it is estimated that the number of cases will increase to 843 million cases by 2050.

- LBP has the highest prevalence globally among musculoskeletal conditions and is the leading cause of disability worldwide.

- LBP is the single leading cause of disability worldwide and the condition for which the greatest number of people may benefit from rehabilitation.

- LBP can be experienced at any age.

- Most people experience LBP at least once in their life.

- Prevalence increases with age up to 80 years, while the highest number of LBP cases occurs at the age of 50–55 years.

- LBP is more prevalent in women.

- LBP can be specific or non-specific.

- Specific LBP is caused by a certain disease or structural problem in the spine that is identifiable.

- Examples of specific LBP would include cancer, infection, fracture, aneurysm, etc.

- Only about 10% of cases of LBP are classified as specific.

- Non-specific LBP is when it is not possible to identify a specific disease or structural reason to explain the pain.

- About 90% of LBP cases are non-specific.

- Chronic LBP is a global public health problem that requires an appropriate response.

•••••

Approximately half of the adults in America suffer from chronic pain (2). Chronic pain affects every region of the body. The most significantly affected region of the body is the low back (3).

The primary syndrome managed by chiropractors, and the primary reason people seek care from chiropractors, is low back pain (LBP). The majority of this LBP is non-specific. There are many scientific theories as to the cause for non-specific LBP, and there are undoubtedly many actual causes for non-specific LBP.

The primary intention of this publication is to present a plausible scientific theory for some (perhaps for many), cases of non-specific LBP, and to present a perspective as to why chiropractic care is so often effective in treating such patients.

•••••

The largest modern review of the chiropractic profession was published in the journal Spine on December 1, 2017, titled (4):

The Prevalence, Patterns, and Predictors of Chiropractic Use Among US Adults Results From the 2012 National Health Interview Survey

The authors of this study note that there are more than 70,000 practicing chiropractors in the United States. Chiropractors use manual therapy to treat musculoskeletal and neurological disorders. The authors state:

“Chiropractic is one of the largest manual therapy professions in the United States and internationally.”

“Chiropractic is one of the commonly used complementary health approaches in the United States and internationally.”

“There is a growing trend of chiropractic use among US adults from 2002 to 2012.”

“Back pain (63.0%) and neck pain (30.2%) were the most prevalent health problems for chiropractic consultations and the majority of users reported chiropractic helping a great deal with their health problem and improving overall health or well-being.”

“Our analyses show that, among the US adult population, spinal pain and problems – specifically for back pain and neck pain – have positive associations with the use of chiropractic.”

“The most common complaints encountered by a chiropractor are back pain and neck pain and is in line with systematic reviews identifying emerging evidence on the efficacy of chiropractic for back pain and neck pain.”

Vertebra Anatomy

The classic image of a lumbar spine (low back) motor unit shows two adjacent vertebrae with the intervertebral disc (IVD) in between the vertebral bodies. What is not typically shown is that between the vertebral bodies and the IVD is a porous cartilaginous end plate.

The IVD is avascular, meaning it has no blood supply to keep the cells and matrix of the disc healthy and functioning well. In contrast, the vertebral bodies are very vascular with an abundant blood supply. The blood in the vertebral bodies, with all of the nutrients, reaches the IVD through the porous cartilaginous end plate. The porous cartilaginous end plate is the main subject of this publication.

Modic Changes

After Michael Modic, MD, graduated medical school in 1975, he completed a Diagnostic Radiology Residency and Neuroradiology Fellowship at the Cleveland Clinic. While at the Cleveland Clinic, he served as Chairman of the Division of Radiology from 1989 through 2006 and Chairman of the Neurological Institute from 2006 through 2015. He is a Fellow of the American College of Radiology and a recipient of the Gold Medal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Imaging. In 2018, Dr. Modic joined Vanderbilt University Medical Center where he is a Professor of Radiology and Radiological Sciences.

Dr. Modic has changed the understanding of chronic low back pain. He and his fellow researchers have established that the pathological changes in the vertebral body end plates are often responsible for the chronic low back pain complaint (5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10). These changes and their classifications are now known as modic changes.

Searching the National Library of Medicine using PUBMED with the search term “modic changes” identifies 1,044 citations (as of February 6, 2025). The first publication was in 1984 (11).

Levers

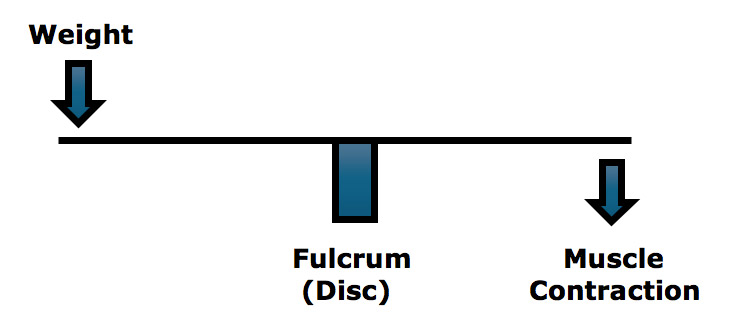

Upright human posture is a first-class lever mechanical system, such as a teeter-totter or seesaw (12, 13).

The fulcrum of a first-class lever is the place where the force is the greatest: if excessively heavy objects are placed on both ends of the teeter-totter, it will break in the middle, at the fulcrum. In the spine, the fulcrum of the first-class lever is the vertebra. Approximately 60% of weight is born by the vertebral body/intervertebral disc/cartilaginous end plate complex, and the other 40% is shared between the two facet joints. This means that when the first-class lever of upright posture is altered, for any reason, there is an increased mechanical load on the cartilaginous end plate.

In their 1990 book Clinical Biomechanics of the Spine (13), White and Panjabi state:

“The load on the discs is a combined result of the object weight, the upper body weight, the back-muscle forces, and their respective lever arms to the disc center.”

In her book Move Your DNA: Restore Your Health Through Natural Movement, biomechanist Katy Bowman clearly explains the difference between weight and load, emphasizing that the real problem is the load, which is the weight multiplied by a lever distance from a fulcrum, and of course adding the counter-balancing efforts of muscles. She states (14):

“The loads created by gravity depend upon our physical position relative to the gravitational force.”

The load created by gravity differs depending on alignment with the “perpendicular force of gravity.”

“It’s not the weight that breaks you down, it’s the load created by the way you carry it.”

All events that increase the load on the IVD will increase the load on the cartilaginous end plate. This is particularly true when the weight is forward (anterior) to the fulcrum. (13)

The constant muscle contraction required to balance the spinal column creates muscle fatigue and myofascial pain syndromes. Rene Cailliet, MD, states “this increase [in muscle tension] not only is fatiguing, but acts as a compressive force on the soft tissues, including the disk [and the cartilaginous end plate]” (12).

The load experienced at the fulcrum (IVD/cartilaginous end plate) of a first-class lever system is dependent upon three factors:

- The magnitude of the weight

- The distance the weight is away from the fulcrum (lever arm)

- The addition of the counterbalancing muscle effort required to remain balanced

This Is Important: In the first publication of the journal Spine, leading spine surgeon and expert Alf Nachemson, MD, clearly shows that the load on the IVD/cartilaginous end plate is 50% higher in the standing forward posture position as compared to the straight erect standing postural position (15).

Forward Posture / Loss of Lumbar Lordosis

Supporting the above discussion is 2005 research published in the journal Spine, titled (16):

The Impact of Positive Sagittal Balance in Adult Spinal Deformity

In this context, “positive sagittal balance” means forward leaning posture secondary to loss of lumbar spinal column lordosis. This would mirror the forward posture increase in the cartilaginous end plate loads as discussed by Dr. Nachemson (15).

This was a multicenter study of 298 adults with anterior forward spinal posture, as measured with full-spine lateral x-rays. Patient pain and health status were measured with standard measurement outcomes.

The authors found that the severity of back symptoms increased in a linear fashion with progressive anterior forward spinal posture. The primary spinal deformity causing the anterior forward spinal posture was loss of lumbar lordosis. Even minor forward posture was detrimental. The authors stated:

“These findings emphasize the importance of thoroughly accessing sagittal plane alignment in the treatment of spinal deformity.”

“There was a high degree of correlation between positive sagittal balance and adverse health status scores, for physical health composite score and pain domain.”

“There was clear evidence of increased pain and decreased function as the magnitude of positive sagittal balance [forward leaning body] increased.”

“This study shows that although even mildly positive sagittal balance is somewhat detrimental, severity of symptoms increases in a linear fashion with progressive sagittal imbalance [forward leaning body].”

The relationship between forward body posture, loss of lumbar lordosis, and the presence of low back pain continues to gain support. In 2017, the journal Spine published an article titled (17):

The Relationships Between Low Back Pain and Lumbar Lordosis:

A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

The authors of this study assessed a total of 13 studies consisting of 796 patients with LBP and 927 healthy controls. They concluded:

“This meta-analysis demonstrates a strong relationship between LBP and decreased lumbar lordotic curvature, especially when compared with age-matched healthy controls.”

The Basivertebral Nerve

The basivertebral nerve is the nerve that innervates the cartilaginous end plate and initiates the pain signal to the brain. This nerve has been proven to be a common source of low back pain (18).

The cartilaginous end plate basivertebral nerve would be irritated and/or inflamed with modic end plate pathological changes. This would increase the pain signal to the brain. These problems would be exacerbated with forward posture loads as explained above.

Corrections / Solutions

Conceptually, interventions that improve forward postural distortions and/or improve lumbar spine lordosis would reduce the irritations and inflammations to the basivertebral nerve. Such approaches to spine care are common-place within the chiropractic profession. They are taught in both undergraduate and postgraduate chiropractic programs.

When spinal forward posture and lumbar lordosis improvements are successful, there is a reduction in non-specific low back pain (19, 20).

REFERENCES

- https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/low-back-pain [June 19, 2023. Accessed February 5, 2025]

- Foreman J; A Nation in Pain, Healing Our Biggest Health Problem; Oxford University Press; 2014.

- Wang S; Why Does Chronic Pain Hurt Some People More?; Wall Street Journal; October 7, 2013.

- Adams J, Peng W, Cramer H, Sundberg T, Moore C; The Prevalence, Patterns, and Predictors of Chiropractic Use Among US Adults; Results From the 2012 National Health Interview Survey; Spine; December 1, 2017; Vol. 42; No. 23; pp. 1810–1816.

- Jensen MC, Brant-Zawadzki MN, Obuchowski N, Modic MT, Malkasian D, Ross JS; Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Lumbar Spine in People Without Back Pain; New England Journal of Medicine; July 14, 1994; Vol. 331; No. 2; pp. 69-73.

- Kjaer P, Leboeuf-Yde C, Korsholm L, Sorensen JS, Bendix T; Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Low Back Pain in Adults: A Diagnostic Imaging Study of 40-Year-Old Men and Women; Spine; May 15, 2005; Vol. 30; No. 10; pp. 1173-1180.

- Bogduk N, Aprill C, Derby R; Lumbar Discogenic Pain: State-of-the-Art Review; Pain Medicine; June 2013; Vol. 14; No. 6; pp. 813–836.

- Bogduk N; Functional Anatomy of the Spine; Handbook of Clinical Neurology; 2016; Vol. 136; pp. 675-688.

- Brinjikji W, Diehn FE, Jarvik GJ, Carr CM, Kallmes DF, Murad MH, Luetmer PH; MRI Findings of Disc Degeneration are More Prevalent in Adults with Low Back Pain than in Asymptomatic Controls: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis; American Journal of Neuroradiology; December 2015; Vol. 36; No. 12; pp. 2394-2399.

- Hancock MJ, Kjaer P, Kent P, Jensen RK, Jensen TS; Is the Number of Different MRI Findings More Strongly Associated With Low Back Pain Than Single MRI Findings?; Spine; September 1, 2017; Vol. 42; No. 17; pp. 1283–1288.

- Modic MT, Hardy RW Jr, Weinstein MA, Duchesneau PM, Paushter DM, Boumphrey F; Neurosurgery: Nuclear Magnetic Resonance of the Spine: Clinical Potential and Limitation; October 1984; Vol. 15; No. 4; pp. 583-592.

- Cailliet R; Low Back Pain Syndrome; 4th edition; F A Davis Company; 1981.

- White AA, Panjabi MM; Clinical Biomechanics of the Spine, Second Edition; Lippincott; 1990.

- Bowman K; Move Your DNA: Restore Your Health Through Natural Movement; Propriometrics Press; 2017.

- Nachemson AL; The Lumbar Spine an Orthopaedic Challenge;

- Spine; March 1976; Vol. 1; No. 1; pp. 59-71.

- Glassman S, Bridwell K, Dimar JR, Horton W, Berven S, Schwab F; The Impact of Positive Sagittal Balance in Adult Spinal Deformity; Spine; September 15, 2005; Vol. 30; No. 18; pp. 2024-2029.

- Chun SW, Lim CY, Kim K, Hwang J, Chung SG; The Relationships Between Low Back Pain and Lumbar Lordosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis; Spine Journal; August 2017; Vol. 17; No. 8; pp. 1180-1191.

- Huang J, Delijani K, Jones J, Di Capua J, Khudari HE, Gunn AJ, Hirsch JA; Basivertebral Nerve Ablation; Seminars in Interventional Radiology; June 30, 2022; Vol. 39; No. 2; pp. 162–166.

- Diab AA, Moustafa IM; Lumbar Lordosis Rehabilitation for Pain and Lumbar Segmental Motion in Chronic Mechanical Low Back Pain: A Randomized Trial; Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics; May 2012; Vol. 35; No. 4; pp. 246-253.

- Oakley PA, Ehsani NN, Moustafa IM, Harrison DE; Restoring Lumbar Lordosis: A Systematic Review of Controlled Trials Utilizing Chiropractic

- Bio Physics® (CBP®) Non-surgical Approach to Increasing Lumbar Lordosis in the Treatment of Low Back Disorders; Journal of Physical Therapy Science; September 2020; Vol. 32; No. 9; pp. 601-610.