Approximately 36 million Americans suffer from migraine headaches. Current pharmacological treatments are not very effective and they may have dangerous side effects (1). Migraines are the second most prevalent neurologic disorder (after tension-type headaches), with a female-to-male ratio of 3:1 and an estimated 1-year prevalence of approximately 15% in the general population (2).

The total sum of suffering caused by migraines is higher than any other kind of headache (3). “Migraine is often incapacitating, with considerable impact on social activities and work, and may lead to significant consumption of drugs.” (3)

The diagnosis of migraines is made clinically. There are no blood tests, imaging, or electro-physiologic tests to establish the diagnosis (3).

The common clinical characteristics of migraine headaches are (4, 5):

- The headache must last 4 to 72 hours.

- The headache must be associated with nausea and/or vomiting, or photophobia, and/or phonophobia.

- The headache must be characterized by 2 of the following 4 symptoms: unilateral location; throbbing pulsatile quality; moderate or worse degree of severity; intensified by routine physical activity.

Chronic migraine is defined as a migraine headache that occurs at least 15 times per month (4, 5).

The migraine diagnosis is assured when these characteristics are present:

- The headache is episodic

- The pain involves half the head

- There is an aura

- There are associated gastrointestinal symptoms

- There is photophobia and/or phonophobia

- The pain is aggravated by the Valsalva maneuver and/or by the head-low position

- The migraine attacks are triggered by the menstrual cycle; fasting; oversleeping; indulgence in alcohol; tyramine-containing foods [meats that are pickled, aged, smoked, fermented; most pork; chocolate; and fermented foods, such as most cheeses, sour cream, yogurt, soy sauce, soybean condiments, teriyaki sauce, tempeh, miso soup, and sauerkraut]

- Migraine relief occurs with sleep

A pioneering study advancing the understanding of all headaches, including migraine headaches, was authored by clinical anatomist and physician, Nikoli Bogduk, MD, PhD, from Australia. Dr. Bogduk’s article was published in the journal Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy in 1995, and titled (6):

Anatomy and Physiology of Headache

In this article, Dr. Bogduk describes the clinical anatomy of headaches, noting that “all headaches have a common anatomy and physiology,” including migraine headaches. Specifically, he states:

“All headaches are mediated by the trigeminocervical nucleus.”

This means that all headaches, including migraine headaches, synapse in the upper aspect of the neck, in a location termed the trigeminocervical nucleus.

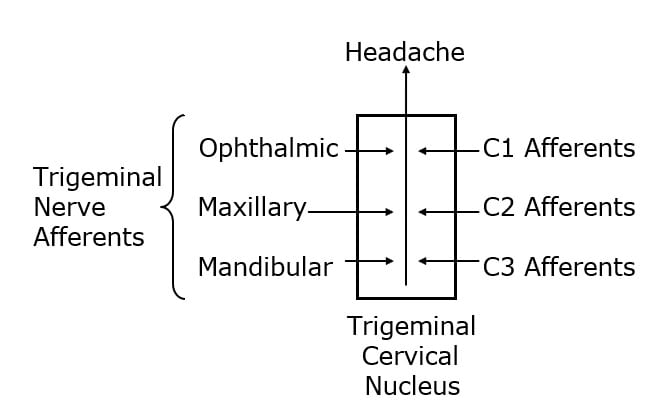

The trigeminocervical nucleus is “defined by its afferent fibers.” The primary afferent fibers that go into the trigeminocervical nucleus are from the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V), and from the upper three cervical nerves (C1, C2, C3). Second order afferent neurons arising in the trigeminocervical nucleus ascend to create an electrical signal in the brain that is interpreted as “headache.”

Disturbances of upper cervical spine afferents may be a source of the electrical signal that is interpreted as a headache in the brain, including migraine headaches. All structures that are innervated by C1, C2, and/or C3, can trigger migraine headaches when irritated and/or inflammed. Such structures include:

- Dura mater of the posterior cranial fossa

- Inferior surface of the tentorium cerebelli

- Anterior and posterior upper cervical and cervical-occiput muscles

- OCCIPUT-C1, C1-C2, and C2-C3 joints

- C2-C3 intervertebral disc

- Vertebral arteries

- Carotid arteries

- Alar ligaments

- Transverse ligaments

- Trapezius muscle

- Sternocleidomastoid muscle

••••••••••

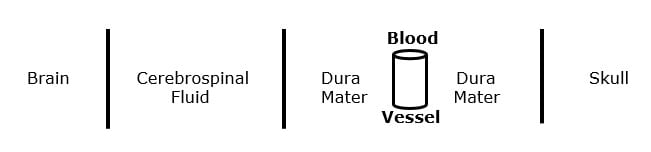

The brain and the spinal cord have a protective layer called the dura mater. The dura mater is attached to the inside of the skull. Between the brain and the dura mater is the cerebral spinal fluid. The cerebral spinal fluid is the critical nutrient bath that nourishes the neurons of the central nervous system.

Important to the discussion of migraine headache is the realization that the dura mater itself contains blood vessels:

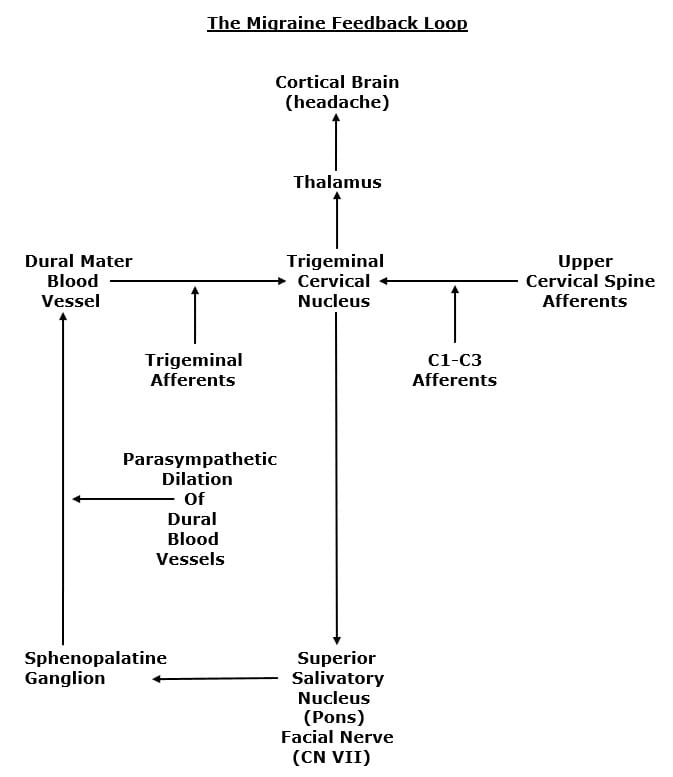

It is proposed that migraine headaches occur when the blood vessels of the dura mater dilate, depolarizing branches of the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V), sending the headache pain electrical signal to the trigeminocervical nucleus, then to the thalamus, then to the cortical brain where the pain is perceived (5, 7).

There is a synaptic communication between the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V) and the facial nerve (cranial nerve VII). The dilation of the dural blood vessels is via the facial nerve (cranial nerve VII), from the parasympathetic production and release of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. The feedback loop involves relays in the superior salivatory nucleus and the sphenopalatine ganglion (5, 7).

Importantly, the entire feedback loop is influenced by the afferent integrity of the upper cervical spine nerve roots (C1-C2-C3). All of this is summarized in the following graph:

••••••••••

In 1978, a study was published in the Australian and New Zealand Journal of Medicine, titled (8):

A Controlled Trial of Cervical Manipulation of Migraine

The efficacy of cervical manipulation for migraine was evaluated in a six-month trial using 85 migraine sufferers. The cervical manipulation was randomly performed by a medical practitioner, a physiotherapist, or chiropractor. The authors stated:

“For the whole sample, migraine symptoms were significantly reduced.”

“Chiropractic patients did report a greater reduction in pain associated with their attacks.”

•••••

In 2000, a study was published in the Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics, titled (9):

A Randomized Controlled Trial of

Chiropractic Spinal Manipulative Therapy for Migraine

This is a randomized controlled trial of 6 months’ duration. The object was to assess the efficacy of chiropractic spinal manipulative therapy in the treatment of migraine. It used 123 subjects (83 manipulation and 40 controls) with a minimum of 1 migraine per month. The majority of subjects had migraines for 18 years (chronic migraines).

The intervention was 2 months of chiropractic diversified technique manipulation at vertebral fixations, with a maximum of 16 visits. The control group received detuned interferential therapy, which consisted of electrodes being placed on the patient with no current sent through the machine. The outcome measures used included frequency, intensity (visual analogue score), duration, disability, and use of medication.

The chiropractic manipulation treatment group “showed statistically significant improvement in migraine frequency, duration, disability, and medication use when compared with the control group.”

- “Twenty-two percent of participants reported more than a 90% reduction of migraines as a consequence of the 2 months of spinal manipulative therapy.”

- “Fifty percent more participants reported significant improvement in the morbidity of each [migraine] episode.”

- 59% “reported no neck pain as a consequence of the 2 months of spinal manipulative therapy.”

- “The results demonstrated a significant reduction in migraine episodes and associated disability.”

- “The greatest area for improvement was [reduced] medication use.”

- “A significant number of participants recorded that their medication use had reduced to zero by the end of the 6-month trial.”

- “It appears probable that chiropractic care has an effect on the physical conditions related to stress and that in these people the effects of the migraine are reduced.”

- “The results of this study support previous results showing that some people report significant improvement in migraines after chiropractic spinal manipulative therapy.”

•••••

In 2014, researchers from Murdoch University in Australia, published a study in the journal Headache, titled (10):

Cervical Referral of Head Pain in Migraineurs:

Effects on the Nociceptive Blink Reflex

This study assessed the pain intensity in 15 migraine subjects with passive movements of the occipital and upper cervical spinal segments. The authors note that anatomically and neurophysiologically there is a functional convergence between the trigeminal and cervical afferent pathways.

Spinal mobilization is applied to dysfunctional areas of the vertebral column. “The clinician’s objective in applying manual techniques is to restore normal motion and normalize afferent input from the neuromusculoskeletal system.” These authors state:

Ongoing noxious sensory input arises from biomechanically dysfunctional spinal joints. Mechanoreceptors including proprioceptors (muscle spindles) within deep paraspinal tissues react to mechanical deformation of these tissues. Manual mechanical deformation can cause “biomechanical remodeling” with restoration of zygapophyseal joint mobility and joint “play.” “Biomechanical remodeling resulting from mobilization may have physiological ramifications, ultimately reducing nociceptive input from receptive nerve endings in innervated paraspinal tissues.”

These findings “corroborate previous results related to anatomical and functional convergence of trigeminal and cervical afferent pathways in animals and humans, and suggest that manual modulation of the cervical pathway is of potential benefit in migraine.”

This study showed that passive manual intervertebral movement between the occiput and the upper cervical spinal joints decreases excitability of the trigeminocervical nucleus. They note that manual cervical modulation of this pathway is of potential benefit in migraine sufferers.

•••••

In 2015, researchers from the United States and Canada published a study in the journal BioMed Research International, titled (11):

Effect of Atlas Vertebrae Realignment in Subjects with Migraine:

An Observational Pilot Study

This study followed 11 subjects who had been diagnosed with migraines by a medical neurologist. The intervention was chiropractic upper cervical vertebrae alignment, delivered over a period of 8 weeks. The authors concluded:

“Study results suggest that the atlas realignment intervention may be associated with a reduction in migraine frequency and marked improvement in quality of life yielding significant reduction in headache-related disability.”

•••••

Also, in 2015, the journal Complementary Therapies in Medicine, published a study titled (12):

Clinical Effectiveness of Osteopathic Treatment in Chronic Migraine:

3-Armed Randomized Controlled Trial

This manipulative therapy trial was the largest ever conducted on adult migraine patients. The authors assessed the effectiveness of manipulative treatment on 105 chronic migraine patients. The authors note:

- The manipulation group was statistically improved from the control and sham group.

- Manipulation “significantly reduced the frequency of migraine.”

- Manipulation “significantly reduced the number of subjects taking medications.”

- Manipulation “showed a significant improvement in the migraineurs’ quality of life.”

- No study participant reported any adverse effects of the manipulation.

- The use of manipulative therapy as an “adjuvant therapy for migraine patients may reduce the use of drugs and optimize the clinical management of the patients.”

- Manipulation “may be considered a clinically valid procedure for the management of patients with migraine.”

•••••

In 2017, researchers from Norway and Australia published a study in the journal Musculoskeletal Science and Practice, titled (13):

Adverse Events in a Chiropractic Spinal Manipulative Therapy:

Single-blinded, Placebo, Randomized Controlled Trial for Migraineurs

This study prospectively reported all adverse events in 70 migraine headache sufferers who were randomized to chiropractic manipulation or a placebo. It used 12 intervention sessions over three months. The authors concluded:

This study “showed significant differences between the chiropractic spinal manipulation group and the control group [drug group] at all post-treatment time points.”

“The risk for adverse events during manual-therapy [is] substantially lower than the risk accepted in any medical context for both acute and prophylactic migraine medication.”

Non-pharmacological management of migraines has the advantage of having mild and transient adverse events, “whereas pharmacological adverse events tend to be continuous.”

“Chiropractic spinal manipulation applying the Gonstead technique appears to be safe for the management of migraine headaches and presents few mild and transient adverse events.”

•••••

In another study from 2017, researchers from Brazil and Spain published an article in the journal European Journal of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, titled (14):

Musculoskeletal Disorders of the Upper Cervical Spine

in Women with Episodic or Chronic Migraine

The objective of this study was to assess the role of musculoskeletal disorders of the cervical spine in association with migraine headaches. The study subjects included 55 women with episodic migraines, 16 with chronic migraines, and 22 matched healthy women.

The assessment included active cervical range of motion, upper cervical spine mobility, and referred pain from upper cervical joints. Women with migraines showed reduced cervical rotation more than healthy women. The authors note:

“Women with migraine exhibit musculoskeletal impairments of the upper cervical spine expressed as restricted cervical rotation, decreased upper cervical rotation, and the presence of symptomatic upper cervical joints.”

The authors concluded that treatment of the musculoskeletal impairments of the cervical spine may help the clinician better manage patients with migraines.

•••••

In 2017, another study from researchers in Germany was published in the journal Cephalalgia, titled (15):

Musculoskeletal Dysfunction in Migraine Patients

The objective of the study was to evaluate the prevalence and pattern of musculoskeletal dysfunctions in migraine patients using a rigorous methodological approach. The authors examined 138 migraine patients (frequent, episodic, and chronic), and 73 age and gender matched healthy controls. The analyses indicated 93% of the migraine patients had at least three musculoskeletal dysfunctions, which was statistically significant different compared to the control subjects. The authors concluded:

“Tests showed a high prevalence of musculoskeletal dysfunctions in migraine patients. These dysfunctions support a reciprocal interaction between the trigeminal and the cervical systems as a trait symptom in migraine.”

•••••

In 2019, a study was published in the journal Headache, titled (16):

The Impact of Spinal Manipulation on Migraine Pain and Disability:

A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

This study is a systematic review and meta-analysis of published randomized clinical trials that evaluate the evidence regarding spinal manipulation as an alternative or integrative therapy in reducing migraine pain and disability. The study analysis included 677 subjects.

The intervention duration ranged from 2 to 6 months, and the number of treatments ranged from 8 to 16. Outcomes included number of migraine days (primary outcome), migraine pain/intensity, and migraine disability. The authors note:

There is a need for evidence-based non-pharmacological approaches to treat migraines, and to “understand whether spinal manipulation, an integral component to chiropractic care, is an effective non-pharmacological approach for the treatment of migraine headaches.”

“One potential non-pharmacological approach to the treatment of migraine patients is spinal manipulation, a manual therapy technique most commonly used by doctors of chiropractic.”

“In this meta-analysis, spinal manipulation was associated with significant reductions in migraine days compared to those in active control groups.”

“Results from this preliminary meta-analysis suggest that spinal manipulation may reduce migraine days and pain/intensity.”

•••••

Also, in 2019, a study was published in the journal Global Advances in Health and Medicine, titled (17):

Integrating Chiropractic Care into the Treatment of Migraine Headaches in a Tertiary Care Hospital: A Case Series

The authors note that chiropractors are licensed to administer nonsurgical and nonpharmacological therapies for health restoration and maintenance. The chiropractic approach to patients suffering with migraine headaches may include combinations of spinal manipulative therapy, soft tissue therapies (myofascial release, massage, trigger point therapies, etc.), rehabilitation/exercises, ergonomic advice, lifestyle management, and nutritional counseling. Chiropractic has “been shown to be efficacious for a wide-range of musculoskeletal conditions including neck pain and temporomandibular pain.” The goals of chiropractic therapy are to optimize neuromusculoskeletal health and reduce the patient’s overall pain burden.

The authors present a three migraine patient case series, noting that integrating neurologic and chiropractic care for the treatment of migraine headaches resulted in:

- Improvement in pain scores

- Increase in pain-free days

- Decreased medication usage

- Patient reports of decreased anxiety/dysthymia

The authors stated:

“All patients reported greater therapeutic benefits with the addition of the integrative approach.”

“Our case series highlights the promise of and the need to further evaluate integrated models of chiropractic and neurologic care.”

Summary

These studies document what essentially every chiropractor has observed for more than a century:

Improvement of the mechanical function of the upper cervical spine with spinal manipulation and other adjunctive mechanical interventions is an effective and safe intervention for patients suffering from migraine headaches.

The benefits of chiropractic spinal manipulation are not only that it is effective and safe, but that it reduces problems associated with pharmacological treatment.

References:

- Lee, SM; Huge Headache of a Problem; Mastering Migraines Still a Challenge for Patients, Scientists; San Francisco Chronicle; July 20, 2014; pp. D1 and D5.

- Stovner LJ, Nichols E, Steiner TJ, et al; Global, regional, and national burden of migraine and tension-type headache, 1990-2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016; Lancet Neurology; 2018; Vol. 17; pp. 954-76.

- Olsen J, Tfelt-Hansen P, Welch KMA; The Headaches, second edition; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000.

- Jones HR; Netter’s Neurology; 2005.

- Ashina M; Migraine; New England Journal of Medicine; November 5, 2020; Vol. 383; pp. 1866-1876.

- Bogduk N; Anatomy and Physiology of Headache; Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy; 1995; Vol. 49; No. 10; pp. 435-445.

- Ashina M, Hansen JM, Do TP, Melo- Carrillo A, Burstein R, Moskowitz MA; Migraine and the trigeminovascular system—40 years and counting; Lancet Neurology; 2019; Vol. 18; pp. 795-804.

- Parker GB, Tupling H, Pryor DS; A controlled trial of cervical manipulation of migraine; Australian and New Zealand Journal of Medicine; December 1978; Vol. 8; No. 6; pp. 589-593.

- Tuchin PJ, Pollard H, Bonello R; A Randomized Controlled Trial of Chiropractic Spinal Manipulative Therapy for Migraine; Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics; February 2000; Vol. 23; No. 2; pp. 91-95.

- Watson DH, Drummond PD; Cervical Referral of Head Pain in Migraineurs: Effects on the Nociceptive Blink Reflex; Headache 2014; Vol. 54; pp. 1035-1045.

- Woodfield HC 3rd, Hasick DG, Becker WJ, Rose MS, Scott JN; Effect of Atlas Vertebrae Realignment in Subjects with Migraine: An Observational Pilot Study; BioMed Research International; December 10, 2015; 630472.

- Cerritelli F, Ginevri L, Messi G, Caprari E, Di Vincenzo M, Renzetti C, Cozzolino V, Barlafante G, Foschi N, Provincial L; Clinical Effectiveness of Osteopathic Treatment in Chronic Migraine: 3-Armed Randomized Controlled Trial; Complementary Therapies in Medicine; April 2015; Vol. 23; No. 2; pp. 149—156.

- Chaibi A, Benth JS, Tuchin PJ, Russell MB; Adverse Events in a Chiropractic Spinal Manipulative Therapy Single-blinded, Placebo, Randomized Controlled Trial for Migraineurs; Musculoskeletal Science and Practice; March 2017; Vol. 29; pp. 66-71.

- Ferracini GN, Florencio LL, Dach F, Bevilaqua Grossi D, Palacios-Ceña M, Ordás-Bandera C, Chaves TC, Speciali JG, Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C; Musculoskeletal Disorders of the Upper Cervical Spine in Women with Episodic or Chronic Migraine; European Journal of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine; June 2017; Vol. 53; No. 3; pp. 342-350.

- Luedtke K, Starke W, May A; Musculoskeletal Dysfunction in Migraine Patients; Cephalalgia; April 2018; Vol. 38; No. 5; pp. 865-875.

- Rist PM, Hernandez A, Bernstein C, Kowalski M, Osypiuk K, Vining R, Long CR, Goertz C, Song R, Wayne PM; The Impact of Spinal Manipulation on Migraine Pain and Disability: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis; Headache; April 2019; Vol. 59; No. 4; pp. 532-542.

- Bernstein C, Wayne PM, Rist PM, Osypiuk K, Hernandez A, Kowalski M; Integrating Chiropractic Care into the Treatment of Migraine Headaches in a Tertiary Care Hospital: A Case Series; Global Advances in Health and Medicine; March 28, 2019; Vol. 8; 2164956119835778.

“Authored by Dan Murphy, D.C.. Published by ChiroTrust® – This publication is not meant to offer treatment advice or protocols. Cited material is not necessarily the opinion of the author or publisher.”