The Piezo1 Mechanoreceptor and Spinal Degenerative Disease

Medicine is primarily about the use of medicines, or chemically based care. Chiropractic is primarily about the use of levers, or mechanically based care. Chiropractors primarily evaluate patients mechanically; they evaluate the manner in which patients stand or sit (posture) and/or move in our gravitational environment.

Mechanical problems can cause stress, irritation, and inflammation in joints, muscles, and nerves, causing symptoms and signs. These symptoms and signs are often treated chemically with drugs, but chemical based care does not correct mechanical problems. Uncorrected mechanical problems cause joint wear and tear, technically known as arthritis, osteoarthritis, spinal degenerative disease, disc degenerative disease, spondylosis, facet arthrosis, etc.

Probably as a consequence of our upright posture, humanity has always suffered from mechanical problems and its joint degenerative consequences (1). Throughout human history, people have sought out mechanical-based care for their mechanical problems, symptoms, and signs (2, 3, 4). This mechanical-based care includes manipulation and other chiropractic-type procedures.

In 2007, a study published in The Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy notes (4):

“Manipulative therapy has known a parallel development throughout many parts of the world. The earliest historical reference to the practice of manipulative therapy in Europe dates back to 400 BCE.”

“Historically, manipulation can trace its origins from parallel developments in many parts of the world where it was used to treat a variety of musculoskeletal conditions, including spinal disorders.”

“It is acknowledged that spinal manipulation is and was widely practiced in many cultures and often in remote world communities such as by the Balinese of Indonesia, the Lomi- Lomi of Hawaii, in areas of Japan, China and India, by the shamans of Central Asia, by sabodors in Mexico, by bone setters of Nepal as well as by bone setters in Russia and Norway.”

“Historical reference to Greece provides the first direct evidence of the practice of spinal manipulation.”

“Hippocrates (460–370 BCE), who is often referred to as the father of medicine, was the first physician to describe spinal manipulative techniques.”

“Claudius Galen (131–202 CE), a noted Roman surgeon, provided evidence of manipulation including the acts of standing or walking on the dysfunctional spinal region.”

“Avicenna (also known as the doctor of doctors) from Baghdad (980–1037 CE) included descriptions of Hippocrates’ techniques in his medical text The Book of Healing.”

Today, the primary formally trained and licensed providers of manual-manipulative mechanical care are chiropractors. There are more than 70,000 licensed chiropractors in the United States, and patient satisfaction with chiropractic care is very high (5). There are 18 colleges/universities that grant chiropractic degrees (DC, for doctor of chiropractic) in the United States (6). In the 1970s, the United States federal government took control of chiropractic education. The United States Department of Education oversees chiropractic education by recognizing the Council for Chiropractic Education (CCE) (6). All 18 of the chiropractic colleges in the United States are accredited by the Council for Chiropractic Education. In addition, all 50 U.S. states grant a license to practice chiropractic to those who have graduated from CCE accredited colleges. The last U.S. state to formally license chiropractors was Louisiana in 1974.

Acknowledging the millennia existence of manual-manipulative mechanical care, the modern trained and licensed providers are much more recent: osteopathy in 1874 and chiropractic in 1895.

Osteopathy began in 1874 by physician Andrew Taylor Still. Dr. Still was a physician and surgeon, author, inventor, and Kansas territorial and state legislator. He was one of the founders of Baker University, the oldest four-year college in the state of Kansas. His interest in mechanical-based care began after the death of all four of his children, acknowledging the limitations of chemical-based care, the awful and frequent side-effects of drug treatments, and the crudeness of surgery of the era. He was the founder of the first School of Osteopathy (Kirksville, MO) in 1897. Dr. Still died in 1917 at the age of 89. Interestingly, the title of one of his four books is (7):

The Philosophy and Mechanical Principles of Osteopathy

Chiropractic began in 1895 by Daniel David Palmer, but was primarily developed by his son, Bartlett Joshua Palmer. BJ Palmer died in 1961 at the age of 78.

Historically, both osteopathy and chiropractic share the importance of mechanical-manipulative care for mechanical problems. In the beginning, both professions encountered resistance from established chemical healthcare providers and their political organizations. Today, this resistance seems senseless in light of the 2021 Nobel Prize in Medicine-Physiology pertaining to biological mechanics.

Early evidence in support of the importance of mechanical-based care includes:

- In 1921, Henry Winsor, MD, used 50 cadavers from the University of Pennsylvania and performed autopsies (necropsies) to determine whether there was any connection between spinal mechanical integrity and neurophysiological function (8). Dr. Winsor found that spinal mechanical stiffness was common, advances with age, and is associated with deleterious neurological function.

- In the 1970s, Princeton University educated physiologist Irvin Korr, PhD, re-affirmed that spinal stiffness and/or aberrant motion altered the mechanical proprioceptive input into the central nervous system (9, 10). This aberrant neurological mechanical input would elicit abnormal spinal cord reflexes and abnormal signals to the brain, resulting in a variety of musculoskeletal dysfunctions.

- In 1985, William H. Kirkaldy-Willis, MD (Professor Emeritus of Orthopedics and director of the Low-Back Pain Clinic at University Hospital, Saskatoon, Canada), proposed that the lack of spinal segmental motion opened the Gate Theory of Pain, resulting in chronic low back and leg pain (11). He showed that using chiropractic spinal adjusting (specific line-of-drive spinal manipulation) would essentially resolve more than 80% of the chronic symptoms and signs.

- In 1986, Vert Mooney, MD (orthopedic surgeon from the University of California, San Diego), was elected president of the International Society for the Study of the Lumbar Spine. His Presidential Address was published in the journal Spine the following year, in which he noted (12):

“In summary, what is the answer to the question of where is the pain coming from in the chronic low-back pain patient? I believe its source, ultimately, is in the disc. Basic studies and clinical experience suggest that mechanical therapy is the most rational approach to relief of this painful condition.”

- In 2003, Donald Ingber, MD, PhD (Vascular Biology Program, Departments of Surgery and Pathology, Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School), noted that mechanical forces are critical regulators of cellular biochemistry and gene expression. He notes that mechanical forces are critical regulators in biology (13). Dr. Ingber states that there is a strong mechanical basis for many generalized medical disabilities, such as lower back pain, which is responsible for a major share of healthcare costs world-wide, and that mechanical interventions can influence cell and tissue function. This would include chiropractic care.

- In 2006, Manohar Panjabi, PhD (Department of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation, Yale University School of Medicine), proposed a new hypothesis to explain chronic back pain (14). He proposed that a single trauma or cumulative microtrauma can cause sub-failure injuries of the ligaments and their embedded mechanoreceptors. These injured mechanoreceptors generate corrupted signals leading to a poor muscle response pattern. This results in abnormal stresses and strains in the ligaments and joints, eventually producing chronic pain. Panjabi emphasizes that the optimal approach to remedy this problem would target the function of the mechanoreceptors.

- In 2010, Apostolos Dimitroulias, MD (Neurosurgical Department, Medical School, Aristotle University, Thessaloniki, Greece), evaluated the presence of mechanoreceptors in human lumbar (L4–5 and L5–S1) intervertebral discs (15). He concluded that there is a large number of mechanoreceptors in these discs in normal human subjects. The role of these mechanoreceptors is the continuous monitoring of position and movement. Abnormal mechanical information will produce muscle spasm, which is an important component of low back pain.

- Also, in 2010, James Wang, PhD, (Mechano-Biology Laboratory, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine) detailed how “Mechanics Rule Cell Biology” (16). Dr. Wang notes that “mechanics play a dominant role in cell biology.” He notes that the therapeutic use of mechanics is critical in improving health and function.

••••

Mechanical-manipulative care is based on the understanding and use of levers, with the understanding that upright human posture is a first-class lever mechanical system (17, 18). When humans lean (tilt), in any direction, muscles contract in a manner to counter-balance the lean, thus keeping the human upright (17, 18).

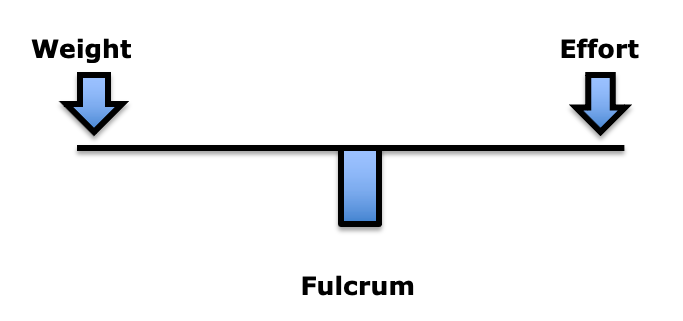

The first-class lever mechanical system has three components:

In the first-class lever mechanical system, the fulcrum is between the weight and the effort. The fulcrum is the site of greatest mechanical stress. In the spine, the fulcrum is the spinal joints, specifically the intervertebral discs and the facet joints. More important than weight is the distance the weight is from the fulcrum. This is load (19). To maintain upright posture, the load must be counterbalanced by effort on the opposite side of the fulcrum. This effort is supplied by muscle contraction.

In summary, the load experienced at the fulcrum of a first-class lever system is dependent upon three factors:

- The magnitude of the weight

- The distance the weight is away from the fulcrum (lever arm)

- The addition of the counterbalancing muscle effort required to remain balanced

This mechanical difference between weight and load are expertly explained in the 2017 book Move Your DNA: Restore Your Health Through Natural Movement, by biomechanist Katy Bowman (19). Bowman maintains that the most important mechanical assessment is to note subtle alterations in alignment.

••••

A modern deleterious alignment epidemic is being caused by the use of cellular mobile phones. This phenomenon is referred to as text neck or tech neck. Recent lay press articles describing text neck include:

- In 2017, Reuters Health published a study titled (20):

Leaning Forward During Phone Use May Cause ‘Text Neck’

- In 2018, The New York Post published a study titled (21):

Tech is Turning Millennials into a Generation of Hunchbacks

Scientific-technical publications describing the epidemiology and causation of text neck include:

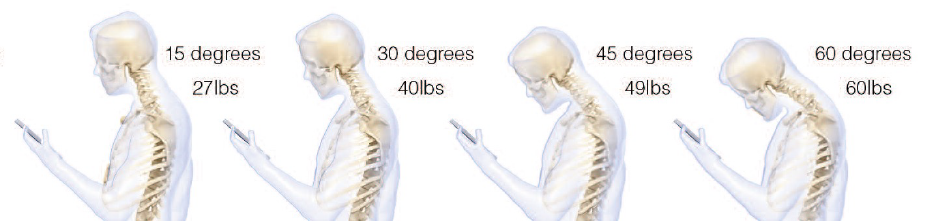

- Rene Cailliet, MD, nicely explains these concepts in his 1996 book Soft Tissue Pain and Disability (22). Dr. Cailliet notes that when a 10 lb. head is displaced forward with a 3-inch lever arm, the counter balancing muscle contraction on the opposite side of the fulcrum (the vertebrae) would have to increase by 30 pounds.

- In 2014, a study was published in the journal Surgical Technology International, titled (23):

Assessment of Stresses in the Cervical Spine Caused by Posture and Position of the Head

The author indicates that the average person spends 2-4 hours a day with their heads tilted forward reading and texting on their smart phones, amassing 700-1400 hours of excess, abnormal cervical spine stress per year. High school students may spend an extra 5,000 hours in poor posture per year. The author calculates the increased mechanical load on the spinal joints caused by this abnormal posture using the first class lever weight-load-counterbalance model described above, concluding:

“Loss of the natural curve of the cervical spine leads to incrementally increased stresses about the cervical spine. These stresses may lead to early wear, tear, degeneration, and possibly surgeries.”

- In 2017, a study was published in the journal Applied Ergonomics, titled (24):

Texting on Mobile Phones and Musculoskeletal Disorders in Young Adults

The study documented that texting on a mobile phone is a risk factor for musculoskeletal disorders in the neck and upper extremities in a population of young adults, aged 20-24 years.

- Also in 2017, a study was published in The Spine Journal, titled (25):

“Text Neck”

An Epidemic of the Modern Era of Cell Phones?

The authors note that extensive cell phone use and associated postures cause spondylotic changes consistent with an aged spine, but they are now being found in younger and younger age groups, including:

- Disc herniations

- Kyphotic alignment

- Abnormal imaging studies

The authors propose that these postures cause significant “chronic increased intradiscal pressure that likely contributes to disk degeneration and herniation.”

- In 2019, a study was published in the journal Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine, titled (26):

The Relationship Between Forward Head Posture and Neck Pain:

A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

This study is a systematic review and meta-analysis that used 15 cross-sectional studies that included 2,339 subjects. It is the first systematic review estimating the relationship between neck pain measures and forward head posture. The authors note that the most common reason for the occurrence of forward head posture is increased time texting on mobile phones or using computers.

- In 2021, a study was published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, titled (27):

Text Neck Syndrome in Children and Adolescents

The authors note that the improper use of personal computers and cell phones might be related to the development of a complex cluster of clinical symptoms commonly defined as “text neck syndrome.” Children and adolescents spend 5 to 7 hours a day on their smartphones and handheld devices with their heads flexed forward to read and text. The cumulative effects of this exposure cause an alarming excess stress to the cervical spinal structures.

••••

The 2021 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to David Julius, PhD, and Ardem Patapoutian, PhD (28, 29). Dr. Julius is a professor and chairman of the department of physiology at the University of California, San Francisco. Dr. Patapoutian is a professor at Scripps Research in La Jolla, California. Their Nobel Prize explained the molecular basis for sensing mechanical forces, including how the body senses position and movement. In particular, their Nobel Prize involved a mechanoreceptor called Piezo1.

In 2022, an article was published in the Journal of Advanced Research, titled (30):

Mechanical Overloading Induces [Glutathione Peroxidase]-Regulated Chondrocyte Ferroptosis in Osteoarthritis via Piezo1 Channel Facilitated Calcium Influx

Using the concepts from the 2021 Nobel Prize, the authors investigated the mechanisms by which aberrant mechanical force on joints would activate the Piezo1 mechanoreceptor and cause articular osteoarthritis.

The authors note that Piezo1 is a mechanically sensitive ion channel that has been extensively studied in both physiological and disease processes. Piezo1 activation leads to cell death and is involved in cartilage degeneration. Suppression of Piezo1 reduces cartilage aging and osteoarthritis.

A simplified model would include these steps:

- Piezo1 is a mechanoreceptor that was mentioned in the 2021 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine.

- Piezo1 mechanoreceptors are found in the membrane of chondrocytes.

- Mechanical loading (overloading) opens the Piezo1 receptor which allows excessive influx of Ca++ to enter into the cell.

- The excessive intracellular Ca++ inhibits glutathione which increases chondrocyte oxidative stress, leading to osteoarthritis.

- Reduction of aberrant mechanical stress on cartilage inhibits Piezo1 mechanoreceptor activation and the downstream consequences leading to cartilage degeneration and osteoarthritis.

Also in 2022, a study was published in the Arthritis Research & Therapy, titled (31):

Excessive Mechanical Stress‑induced Intervertebral Disc Degeneration is Related to Piezo1 Overexpression Triggering the Imbalance of Autophagy/Apoptosis in Human Nucleus Pulposus

The authors investigated the consequences of human cervical spine kyphosis on the Piezo1 mechanoreceptor as related to intervertebral disc degeneration. Cervical lordosis was assessed with x-rays using the protocol established by Deed Harrison, DC, and colleagues in the journal Clinical Biomechanics in 2001 (32). This point should be emphasized: 2021 Nobel Prize concepts being investigated using mechanical research by chiropractors.

The authors reiterate that mechanical stress plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of intervertebral disc degeneration, noting:

“Intervertebral disc degeneration is the leading cause of degenerative spine diseases such as discogenic pain and disc herniation, which reduces the quality of life and increases the socioeconomical burden.”

Compressive forces by bad postures or kyphosis leads to intense stresses that act on the nucleus pulposus and activate the Piezo1 mechanoreceptor, using the following model:

- Cervical kyphosis increases the load on the Piezo1 mechanoreceptor.

- The activation of Piezo1 opens the calcium ion channel, activating a sequence of events leading to cell death and soft tissue stiffness.

Mechanical providers of care have helped patients for millennia. In the modern era, mechanical healthcare began in 1874 with the start of osteopathy. Since 1895, in the United States and other countries around the world, the primary providers for mechanical care are chiropractors. Mechanical care influences mechanoreceptors, especially the Piezo1 receptor, which was a part of the 2021 Nobel Prize in Medicine or Physiology. Since the award of the 2021 Nobel Prize, studies continue to support the value of mechanical-based care as practiced by chiropractors, especially for the prevention and management of joint degenerative disease and associated pain syndromes.

REFERENCES

- Kendall HO, Kendall FP, Boynton DA; Posture and Pain; Williams & Wilkins; 1985.

- Morgan M; Mutant Message Down Under; 1990.

- Anderson R; “Spinal Manipulation Before Chiropractic”; in Haldeman S; Principles and Practice of Chiropractic; Second Edition; Appleton & Lang; 1992.

- Pettman E; A History of Manipulative Therapy; The Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy; 2007; Vol. 15; No. 3; pp. 165–174.

- Adams J, Peng W, Cramer H, Sundberg T, Moore C; The Prevalence, Patterns, and Predictors of Chiropractic Use Among US Adults; Results From the 2012 National Health Interview Survey; Spine; December 1, 2017; Vol. 42; No. 23; pp. 1810–1816.

- cce-usa.org; accessed July 4, 2023.

- Still AT; The Philosophy and Mechanical Principles of Osteopathy; Hudson Kimberley Pub. Co; Kansas City, MO; 1892 and 1902.

- Winsor H; Sympathetic Segmental Disturbances: The Evidences of the Association, in Dissected Cadavers, of Visceral Disease with Vertebral Deformities of the Same Sympathetic Segments; Medical Times; November 1921; pp. 1-7.

- Korr IM; Proprioceptors and Somatic Dysfunction; Journal of the American Osteopathic Association; March 1975; Vol. 74; No. 7; pp. 638-650.

- Korr IM; The Spinal Cord as Organizer of Disease Process III: Hyperactivity of Sympathetic Innervation as a Common Factor in Disease; Journal of the American Osteopathic Association; December 1979; Vol. 79; No. 4; pp. 232-237.

- Kirkaldy-Willis WH, Cassidy JD; Spinal Manipulation in the Treatment of Low Back Pain; Canadian Family Physician; March 1985; Vol. 31; pp. 535-540.

- Mooney V; Where Is the Pain Coming From?; Spine; October 1987; Vol. 12; No. 8; pp. 754-759.

- Ingber DE; Mechanobiology and Diseases of Mechanotransduction; Annals of Medicine; 2003; Vol. 35; No. 8; pp.564-577.

- Panjabi MM; A hypothesis of chronic back pain: Ligament subfailure injuries lead to muscle control dysfunction; European Spine Journal; May 2006; Vol. 15; No. 5; pp. 668-676.

- Dimitroulias A, Tsonidis C, Natsis K, Venizelos I, Djau SN. Tsitsopoulos P; An immunohistochemical study of mechanoreceptors in lumbar spine intervertebral discs; Journal of Clinical Neuroscience; June 2010; Vol. 17; No 6; pp. 742-745.

- Wang J, Bin Li; Mechanics Rule Cell Biology; Sports Medicine, Arthroscopy, Rehabilitation, Therapy & Technology; 2010; Vol. 2; No. 16.

- White AA, Panjabi MM; Clinical Biomechanics of the Spine; Second Edition; Lippincott; 1990.

- Cailliet R; Soft Tissue Pain and Disability; 3rd Edition; FA Davis Company; 1996.

- Bowman K; Move Your DNA: Restore Your Health Through Natural Movement; Propriometrics Press; 2017.

- Crist C; Leaning forward during phone use may cause ‘text neck’; Reuters Health; April 14, 2017.

- Fleming K; Tech is Turning Millennials Into a Generation of Hunchbacks; The New York Post; March 5, 2018.

- Cailliet R; Soft Tissue Pain and Disability; 3rd Edition; FA Davis Company; 1996.

- Hansraj KK; Assessment of Stresses in the Cervical Spine Caused by Posture and Position of the Head; Surgical Technology International; November 2014; Vol. 25; pp. 277-279.

- Gustafsson E, Thoee S, Grimby-Ekman A, Hagberg M; Texting on Mobile Phones and Musculoskeletal Disorders in Young Adults: A Five-year Cohort Study; Applied Ergonomics; January 2017; Vol. 58; pp. 208-214.

- Cuéllar JM, Lanman TH; “Text Neck” An Epidemic of the Modern Era of Cell Phones?; The Spine Journal; June 2017; Vol. 17; No. 6; pp. 901–902.

- Mahmoud NF, Hassan KA, Abdelmajeed SF, Moustafa IM, Silva AG; The Relationship Between Forward Head Posture and Neck Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis; Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine; December 2019; Vol. 12; No. 4; pp. 562-577.

- David D, Giannini C, Chiarelli F, Mohn A; Text Neck Syndrome in Children and Adolescents; International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health; February 7, 2021; Vol. 18; No. 4; Article 1565.

- Roland D, Abott B; Nobel Prize in Medicine Awarded for Work on Senses; Wall Street Journal; October 5, 2021.

- Zylka MJ; A Nobel Prize for Sensational Research; New England Journal of Medicine; December 16, 2021; Vol. 385; No. 25; pp. 2393-2394.

- Wang S, Li W, Zhang P, 13 more; Mechanical Overloading Induces [Glutathione Peroxidase]-Regulated Chondrocyte Ferroptosis in Osteoarthritis via Piezo1 Channel Facilitated Calcium Influx; Journal of Advanced Research; 2022; Vol 41; pp. 63–75.

- Shi S, Kang XJ, Zhou Z, He ZM, Zheng S, He SS; Excessive Mechanical Stress‑induced Intervertebral Disc Degeneration is Related to Piezo1 Overexpression Triggering the Imbalance of Autophagy/Apoptosis in Human Nucleus Pulposus; Arthritis Research & Therapy; May 23, 2022; Vol. 24; No. 1; Article 119.

- Harrison DE, Harrison DD, Janik TJ, William Jones E, Cailliet R, Normand M; Comparison of axial and flexural stresses in lordosis and three buckled configurations of the cervical spine; Clinical Biomechanics; May 2001; Vol.16; No. 4; pp. 276–784.