The Numbers

Low back pain is one of the most thoroughly investigated health problems worldwide, yet both prevention and effective treatment are elusive and controversial. The National Library of Medicine of the United States displays nearly 25,000 articles when the key words “low back pain” are used (May 2014).

Suffering with low back pain is almost a universal human experience. The United Stated Government’s National Institutes of Health (NIH) has the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, which has a Low Back Pain Fact Sheet (1). The Fact Sheet makes the following key points:

- Nearly everyone at some point will have back pain.

- Americans spend at least $50 billion each year on low back pain.

- Back pain is the most common cause of job-related disability and a leading contributor to missed work.

- Back pain is the second most common neurological ailment in the United States — only headache is more common.

Public Health statistics (as of April 2014) add the following key points (2):

- Low back pain (LBP) is a major public health problem worldwide.

- All age groups are affected with low back pain, including children and adolescents.

- 1%–2% of adults in the United States are disabled with low back pain.

- The morbidity toll attributed to low back pain is enormous from both personal and societal perspectives.

- Direct back pain health-care expenditures in the United States were $90.7 billion in 1998. The burden is even greater when indirect costs such as productivity losses, indemnity pay, litigation, retraining and other administrative costs are considered.

- Only heart disease and stroke have substantially higher medical expenditures than spine disorders in the United States.

- LBP is presently the leading cause of disability in the world.

- LBP is the leading cause of activity limitation and workplace absence in most parts of the world.

- Most people will experience LBP at some point in their lifetime, with two-thirds having a recurrence and one third having periods of disability.

- Cases in which LBP never recurs are rare.

- A previous episode of back pain is the primary risk factor for a new LBP episode.

Global Spinal Anatomy

The Compromise Between Movement and Strength

The spinal column has three main functions:

- To be strong in gravity. To resist the compressive loads of our weight and to successfully transmit our weight loads to the legs.

- To be flexible as to allow us to perform the activities of life: bending, stooping, lifting, work, play, sports, enhance seeing and hearing, etc.

- To protect the nerves of the spinal cord.

The strongest structure is a column. This is why engineers use columns to support bridges and buildings. However, a column is a poor design for the spine because columns limit motion (like turning and bending).

The most efficient structure for allowing movement is a 90° lever, like a lug-wrench.

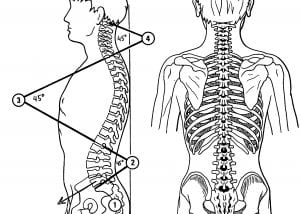

The spinal “column” is a compromise between strength (straight column) and mobility (90° lever), with a series of three curves of about 45° each. Without these curves, spinal motion would be extremely difficult. These curves are physiologically important and considered to be normal.

Consequently, from the side, the spinal “column” should have three curves. From behind, the spine should be straight.

Segmental Spinal Anatomy

To further enhance spinal mobility, the spinal “column” is compromised of 24 individual segments, called vertebrae, each with a small degree of normal motion in multiple directions. Collectively, these small amounts of motion add up to our significant spinal flexibility.

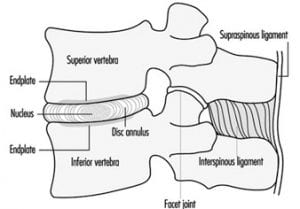

Two adjacent spinal vertebrae are called a motor unit.

The individual vertebrae of the motor unit are held together by ligaments and by the intervertebral disc, or simply “disc.”

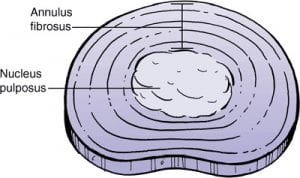

The intervertebral disc (disc) requires more discussion. The disc has two components. The center of the disc is called the Nucleus Pulposus, or simply “nucleus.” The nucleus is mostly water and functions as a ball bearing, allowing the vertebrae to bend and twist.

The nucleus is surrounded by tough outer fibers called the Annulus Fibrosis, or simply “annulus.”

The annular fibers surround the nucleus like layer after layer of rubber bands. Like rubber bands, annular fibers can break with age or excessive mechanical stress. When this occurs, the nucleus is no longer held in place, and its ball bearing functions are reduced.

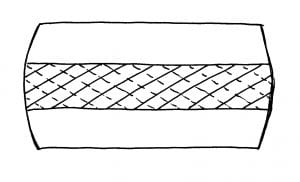

Importantly, the fibers of the annulus are arranged in layers, and each layer is crossed in opposite directions. During disc rotational movements, half of the annular fibers become tense, and the other half become lax. Rotational stress applied to the annulus is resisted by only half of the annular fibers. The disc is operating at only half strength during rotationally applied stress, increasing its vulnerability to injury. The disc is weakest during rotation. It is the integrity of the disc that is most responsible for the health of the spine.

Crossed Annular Fibers of the Intervertebral Disc

Intervertebral Disc Pressure

The vertebral body of the spine is designed to bear our weight. Consequently, the size of the vertebral body increases with each lower vertebrae, from the neck to the low back, to handle the increased weight. The disc, existing between adjacent vertebral bodies, also must bear the same weight. Yet, the disc is not made of bone and is consequently weaker. Also, the disc must be flexible, allowing for our bodily motions.

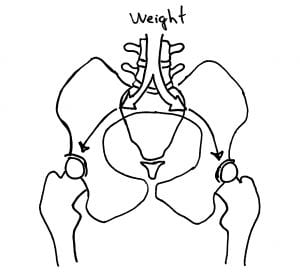

The last low back (lumbar) disc, known as the L5 disc, bears the most weight, and hence is most vulnerable to weight-bearing stress. After L5, our weight is split to go down both of our legs.

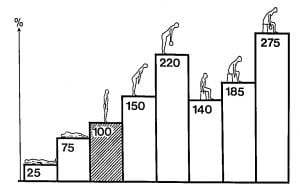

The L5 (last low back) disc has the greatest pressure. In addition, disc pressure changes with changes in bodily positions and activities. Pioneering Swedish orthopedic specialist and professor Alf Nachemson, MD, PhD, [1931-2006] developed a method to measure intradiscal pressures (3).

Using relative values for easy comparison, note the following:

- Disc pressure is lowest when lying on the back. Perhaps this is why lying on the back is the most comfortable position for patients suffering with low back pain.

- Disc pressure is four times greater when standing as compared to lying on ones back.

- Standing and bending forward increases disc pressure by 50% compared to standing straight. Perhaps this is why so many patients initiate their back pain by bending forward.

- Disc pressures are significantly higher when standing, bending forward, and holding a weight, increasing by more than 100%. The heavier the weight is, the greater the increase in intradiscal pressures, and the greater the risk of disc injury.

- Disc pressures are greatest while sitting. Prolonged sitting is bad for the disc.

- Disc pressure is maximum during sitting, bending forward, and holding a weight.

The Inclined Plane of L5

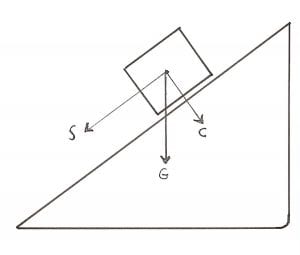

In the reference text The Physiology of the Joints, former Chief of Clinical Surgery at the Hospital of Paris, IA Kapandji, states (4):

“The lumbo-sacral joint is the weak link in the vertebral column.”

When a block is on an inclined plane, the vertical force of gravity (G) is broken into two vectors:

C – A compression component

S – A sheer component

The sacral base is not horizontal (flat), but rather it is an inclined plane. The L5 vertebral body sits atop of the inclined plane of the sacral base. This inclined plane places additional mechanical stress on the annulus of the L5 disc.

Where Does Back Pain Come From?

The modern era in the understanding of low back pain began in 1976 when internationally respected orthopedic surgeon Alf Nachemson published his detailed review (136 references) in the new journal SPINE, titled (3):

The Lumbar Spine: An Orthopaedic Challenge

Based in part on his intradiscal pressure studies, Dr. Nachemson notes that 80% of us will experience low back pain at some time in our life. He further notes that:

“The intervertebral disc is most likely the cause of the pain.”

Dr. Nachemson presents 6 lines of reasoning, supported by 17 references, to support his contention that the intervertebral disc is the most likely source of back pain. Nachemson was claiming that a non-herniated disc problem was causing back pain. At the time (1976), claiming the intervertebral disc was capable of initiating pain was new; claiming the disc to be the most probable source of back pain was revolutionary. Up until the late 1980s, most reference texts were claiming that the intervertebral disc was not innervated with pain afferents and therefore not capable of initiating pain. As an example, in the 1987 text edited by rheumatology professor Malcolm Jayson, MD, titled The Lumbar Spine and Back Pain, states “the mature human spine has no nerve endings of any description in the nucleus pulposus or annulus fibrosis of the intervertebral disc in any region of the vertebral column.” (5)

In 1981, anatomist and physician Nikoli Bogduk published an extensive review of the literature on the topic of disc innervation, along with his own primary research, in the prestigious Journal of Anatomy (6). Dr. Bogduk notes:

“In the absence of any comprehensive description of the innervation of the lumbar intervertebral discs and their related longitudinal ligaments, the present study was undertaken to establish in detail the source and pattern of innervation of these structures.”

“The lumbar intervertebral discs are supplied by a variety of nerves.”

“Clinically, the concept of ‘disc pain’ is now well accepted.”

In 1983, in SPINE, Dr. Bogduk updates his research, stating (7):

“The lumbar intervertebral discs are innervated posteriorly by the sinuvertebral nerves, but laterally by branches of the ventral rami and grey rami communicantes.”

“The distribution of the intrinsic nerves of the lumbar vertebral column systematically identifies those structures that are potential sources of primary low-back pain.”

In 1987, SPINE published Dr. Vert Mooney’s Presidential Address of the International Society for the Study of the Lumbar Spine. It was delivered at the 13th Annual Meeting of the International Society for the Study of the Lumbar Spine, May 29-June 2, 1986, Dallas, Texas, and noted (8):

“Persistent pain in the back with referred pain to the leg is largely on the basis of abnormalities within the disc.”

“In summary, what is the answer to the question of where is the pain coming from in the chronic low-back pain patient? I believe its source, ultimately, is in the disc.”

In 1991, primary research by Dr. Stephen Kuslich and colleagues was published in the journal Orthopedic Clinics of North America (9). The authors performed 700 lumbar spine operations using only local anesthesia to determine the tissue origin of low back and leg pain, and they present the results on 193 consecutive patients studied prospectively. Their findings included:

“Back pain could be produced by several lumbar tissues, but by far, the most common tissue or origin was the outer layer of the annulus fibrosis.”

Hyper-innervation

Receptive Field Enlargement

Beginning with the work of Nikoli Bogduk and others over the past three decades, there has been a growing acceptance that the annulus of the disc is innervated with pain afferents and the annulus of the disc is the most probable source for low back pain. There was also 100% agreement that the nerves were only found in the annulus, and that the nucleus was aneural. However, an important addition to these concepts arose in 1997.

In 1997, AJ Freemont and colleagues published a study in the journal Lancet, titled (10):

Nerve ingrowth into diseased intervertebral disc in chronic back pain

Using samples of the intervertebral discs from 38 humans, these authors were able to show that when the disc degenerates, the nerves in the annulus can migrate into the nucleus. Histologically, these nerves in the nucleus were judged to be pain afferents. Thus the nucleus itself could be a source of discogenic pain. These authors used these anatomical findings to explain why low back pain can be so chronic, and continue to add to the evidence that the disc is the primary source of low back pain.

Later in 1997, in the journal Spine, another study was published on the topic of nucleus innervation, and titled (11):

Innervation of “painful” lumbar discs

The authors, in agreement with Freemont and colleagues, also found nerves in the nucleus of human subjects with disc degeneration.

Summary

There has been mounting evidence, for decades, that the disc has pain nerves, allowing the disc to be the primary source of low back pain. The disc also has unique susceptibility to injury, stress, and inflammation, initiating the pain cascade:

- The disc is innervated with an extensive array of pain nerves.

- The lower spinal discs, especially the L5 disc, is a significant part of the weight-bearing mechanism. Structures that bear weight have a greater risk and incidence of degenerative change.

- The L5 disc exists on a significant inclined plane, increasing its risk for motion stress and subsequent degeneration and injury.

- The annular fibers of the disc are crossed in opposite directions. This reduces the strength of the disc during certain activities, increasing its risk for motion stress and subsequent degeneration and injury.

- Varying body postures and activities increase the pressure in the disc, increasing its risk for motion stress and subsequent degeneration and injury.

- With disc degeneration, there is an increase in the number of pain fibers in the disc, including into the nucleus itself. The increase in the number of pain nerve fibers increases the likelihood that stress and injury will produce low back pain.

Practical Solutions To Avoid Low Back Pain

Practical Solutions to Manage Existing Low Back Pain

- The single worse activity for one’s back is to lift something while bending and twisting. Twisting reduces the strength of the annulus by 50%. Both bending and lifting significantly increase the pressure in the disc.

- Excessive body weight adds to the pressure and wear-and-tear on the disc.

- Prolonged sitting and primary sitting occupations are bad for the disc. Sitting places 40% more pressure and stress on the disc as compared to standing.

- Keep the back mobile, supple. The disc has no blood supply, so the health of its cells depends upon motion that pumps fluid into the disc. Discs with poor nutrients become inflamed and painful. Practice techniques that help the spine to be flexible; these same techniques literally pump fluid with fresh nutrients into the disc, much like squeezing a dry sponge under water. See a chiropractor to safely maximize spinal disc joint mobility.

- Do NOT smoke. Smoking impairs disc nutrition and accelerates disc degeneration.

- Keep the back muscles strong. Most critical for back pain treatment and prevention is an exercise concept called CORE STABILIZATION. Spine care experts, like chiropractors, can custom design a core stabilization program for optimal spine care.

- Maintain good posture. Poor posture increases disc pressure and degeneration. Individual static adverse postural distortions can be improved or corrected with chiropractic spinal care, corrective exercises, and spinal molding.

REFERENCES

- www.ninds.nih.gov; Low Back Pain Fact Sheet; accessed May 12, 2014.

- Vassilaki M, Hurwitz EL; Insights in Public Health: Perspectives on Pain in the Low Back and Neck: Global Burden, Epidemiology, and Management; Hawaii J Med Public Health. Apr 2014; 73(4): 122–126.

- Nachemson AL, Spine, Volume 1, Number 1, March 1976, pp. 59-71.

- Kapandji IA; The Physiology of the Joints; Volume Three, The Trunk and the Vertebral Column; Churchill Livingstone; 1974.

- Jayson M, Editor; The Lumbar Spine and Back Pain, Third Edition, Churchill Livingstone, 1987, p. 60.

- Bogduk N, Tynan W, Wilson AS; The nerve supply to the human lumbar intervertebral discs, Journal of Anatomy; 1981; Vol. 132; No. 1, pp. 39-56.

- Bogduk N., The innervation of the lumbar spine; Spine; April 1983;8(3): pp. 286-93.

- Mooney, V, Where Is the Pain Coming From? Spine, 12(8), 1987, pp. 754-759.

- Kuslich S, Ulstrom C, Michael C; The Tissue Origin of Low Back Pain and Sciatica: A Report of Pain Response to Tissue Stimulation During Operations on the Lumbar Spine Using Local Anesthesia; Orthopedic Clinics of North America, Vol. 22, No. 2, April 1991, pp. 181-7

- Freemont AJ, Peacock TE, Goupille P, Hoyland JA, O’Brien J, Jayson MI; Nerve ingrowth into diseased intervertebral disc in chronic back pain; Lancet; Jul 19, 1997;350(9072):178-81.

- Coppes MH, Marani E, Thomeer RT, Groen GJ; Innervation of “painful” lumbar discs; Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1997 Oct 15;22(20):2342-9.