In 1934, William Jason Mixter, MD and Joseph S Barr, MD, published a study in the New England Journal of Medicine (1) establishing that the rupture of the intervertebral disc could result in pressure on the related nerves, causing back and leg pain. In this study, Drs. Mixter and Barr also suggested that the lumbar intervertebral disc could be the source of lower back pain without compressing a nerve root.

In 1947, Vern T Inman, MD and JBM Saunders added to the concept of discogenic lower back pain. In their study, published in the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (2), they suggested that discogenic lower back pain was as a consequence of “sclerotogenous” referral, thus anatomically accounting for the diffuse nonspecific nature of the lower back pain complaint. Sclerotogenous pain is different than dermatomal (skin) and myotomal (muscle) pain. Sclerotogenous pain is a referred pain that occurs when there is a sensory irritation to a structure that shared embryological mesodermal innervation. Drs. Inman and Saunders note that the disc itself can be the source of local pain and sclerotogenous referred pain, even in the absence of nerve root pressure. They state:

“The annulus fibrosis has been shown to possess a rich sensory nerve supply.”

“There is now abundant experimental evidence to support the contention that distortion of the annulus fibrosus and related ligamentous structures of the neighboring joint, is in itself the source of pain of a characteristic type which, depending upon the level involved, may be referred to fairly specific areas of the body.”

The first issue of the journal Spine was published in March 1976. From its humble beginnings, nearly 35 years ago, Spine has risen to become the world’s top ranked orthopedic journal. Spine is now the official journal of publication for the world’s top fourteen orthopedic societies.

In the inaugural March 1976 issue of Spine (3), internationally respected orthopedic surgeon Alf Nachemson, MD, published his detailed review (136 references) pertaining to the state of knowledge on the topic of lower back pain. At the time, Dr. Nachemson’s article was considered to be the most comprehensive and authoritative review available on the topic of low back pain, and it remains extensively cited in contemporary publications. Dr. Nachemson titled his article:

The Lumbar Spine: An Orthopaedic Challenge

In this article, Dr. Nachemson notes that 80% of us will experience low back pain at some time in our life. He further notes that:

“The intervertebral disc is most likely the cause of the pain.”

Dr. Nachemson presents 6 lines of reasoning and cites 17 references to support his contention that the intervertebral disc is the most likely source of lower back pain. One of the studies cited by Dr. Nachemson was the primary research completed by Smyth and Wright in 1958 (4). Regarding the work by Smyth and Wright, Dr. Nachemson notes:

“Investigations have been performed in which thin nylon threads were surgically fastened to various structures in and around the nerve root. Three to four weeks after surgery these structures were irritated by pulling on the threads, but [lower back] pain resembling that which the patient had experienced previously could be registered only from the outer part of the annulus” of the disc.

In 1976, Dr. Alf Nachemson was considered the world’s leading authority on low back pain and on the lumbar spine. However, claiming that a non-herniated disc problem was the primary cause of back pain was novel, controversial, and contentious. At the time (1976), claiming the intervertebral disc was capable of initiating pain was not widely accepted, and claiming the non-herniated intervertebral disc to be the most probable source of back pain was revolutionary. At the time, most authoritative reference texts were claiming that the intervertebral disc was not innervated with pain afferents and therefore not capable of initiating pain. As an example, the 1987 text edited by rheumatology professor Malcolm Jayson, MD, titled The Lumbar Spine and Back Pain, states “the mature human spine has no nerve endings of any description in the nucleus pulposus or annulus fibrosis of the intervertebral disc in any region of the vertebral column.” (5)

Support for Dr. Nachemson’s contention of disc pain came in 1981 when Australian clinical anatomist and physician Nikoli Bogduk published an extensive review of the literature on the topic of disc innervation, along with his own primary research, in the prestigious Journal of Anatomy (6). Dr. Bogduk states:

“In the absence of any comprehensive description of the innervation of the lumbar intervertebral discs and their related longitudinal ligaments, the present study was undertaken to establish in detail the source and pattern of innervation of these structures.”

“The lumbar intervertebral discs are supplied by a variety of nerves.”

“Clinically, the concept of ‘disc pain’ is now well accepted.”

In 1983, in the journal Spine, Dr. Bogduk updates his research pertaining to the neurological innervation of the intervertebral disc and its relationship to lower back pain. Dr. Bogduk states (7):

“The lumbar intervertebral discs are innervated posteriorly by the sinuvertebral nerves, but laterally by branches of the ventral rami and grey rami communicantes. The posterior longitudinal ligament is innervated by the sinuvertebral nerves and the anterior longitudinal ligament by branches of the grey rami. Lateral and intermediate branches of the lumbar dorsal rami supply the iliocostalis lumborum and longissimus thoracis, respectively. Medial branches supply the multifidus, intertransversarii mediales, interspinales, interspinous ligament, and the lumbar zygapophysial joints.”

“The distribution of the intrinsic nerves of the lumbar vertebral column systematically identifies those structures that are potential sources of primary low-back pain.”

As noted, Dr. Bogduk is adding to the establishment that the lumbar intervertebral disc is innervated, and that this innervation allows the disc to become a source of pain perception.

In 1987, the journal Spine published Dr. Vert Mooney’s Presidential Address of the International Society for the Study of the Lumbar Spine. It was delivered at the 13th Annual Meeting of the International Society for the Study of the Lumbar Spine, May 29-June 2, 1986, in Dallas, Texas. The title of Dr. Mooney’s address was (8):

Where Is the Pain Coming From?

In this article, Dr. Mooney notes the following:

“Six weeks to 2 months is usually enough to heal any stretched ligament, muscle tendon, or joint capsule. Yet we know that 10% of back ‘injuries’ do not resolve in 2 months and that they do become chronic.”

“Anatomically the motion segment of the back is made up of two synovial joints and a unique relatively avascular tissue found nowhere else in the body – the intervertebral disc. Is it possible for the disc to obey different rules of damage than the rest of the connective tissue of the musculoskeletal system?”

“Persistent pain in the back with referred pain to the leg is largely on the basis of abnormalities within the disc.”

Chemistry of the disc is based on the relationship between mucopolysaccharide production and water content.

“Mechanical events can be translated into chemical events related to pain.”

An important aspect of disc nutrition and health is the mechanical aspects of the disc related to the fluid mechanics.

“Mechanical activity has a great deal to do with the exchange of water and oxygen concentration” in the disc.

The pumping action maintains the nutrition and biomechanical function of the intervertebral disc. Thus, “research substantiates the view that unchanging posture, as a result of constant pressure such as standing, sitting or lying, leads to an interruption of pressure-dependent transfer of liquid. Actually the human intervertebral disc lives because of movement.”

“The fluid content of the disc can be changed by mechanical activity, and the fluid content is largely bound to the proteoglycans, especially of the nucleus.”

“In summary, what is the answer to the question of where is the pain coming from in the chronic low-back pain patient? I believe its source, ultimately, is in the disc. Basic studies and clinical experience suggest that mechanical therapy is the most rational approach to relief of this painful condition.”

“Prolonged rest and passive physical therapy modalities no longer have a place in the treatment of the chronic problem.”

The model presented by Dr. Mooney in this paper includes:

The intervertebral disc is the primary source of both back pain and referred leg pain. The disc becomes painful because of altered biochemistry, which sensitizes the pain afferents that innervate it. Disc biochemistry is altered because of mechanical problems, especially mechanical problems that reduce disc movement. Therefore, the most rational approach to the treatment of chronic low back pain is mechanical therapy that restores the motion to the joints of the spine, especially to the disc. Prolonged rest is inappropriate management for discogenic lower back pain.

Additional support for the disc being the primary source of lower back pain was presented by Dr. Stephen Kuslich and colleagues in the prestigious journal Orthopedic Clinics of North America in April 1991 (9). The title of their article is:

The Tissue Origin of Low Back Pain and Sciatica:

A Report of Pain Response to Tissue Stimulation During Operations on the Lumbar Spine Using Local Anesthesia

The authors performed 700 lumbar spine operations using only local anesthesia to determine the tissue origin of low back and leg pain. In this study, Dr. Kuslich and colleagues present the results on 193 consecutive patients they studied prospectively. Several of their important findings include:

“Back pain could be produced by several lumbar tissues, but by far, the most common tissue of origin was the outer layer of the annulus fibrosis.”

The lumbar fascia could be “touched or even cut without anesthesia,” without producing any pain.

Any pain derived from muscle pressure was “derived from local vessels and nerves, rather than the muscle bundles themselves.”

“The normal, uncompressed, or unstretched nerve root was completely insensitive to pain.”

“In spite of all that has been written about muscles, fascia, and bone as a source of pain, these tissues are really quite insensitive.”

In summary, these authors found the outer annulus of the intervertebral disc to be “the site” of a patient’s chronic back pain. Studies that suggest the disc is not an important source of low back pain because nerve endings are not present are mistaken, wrong. Irritation of a normal or inflamed nerve root never produced low back pain. Back muscles themselves are not a source of back pain; in fact, the muscles, fascia, and bone are really quite insensitive to pain. Also the inflamed, stretched, or compressed nerve root is the cause of buttock, leg pain and sciatica, but not back pain. Not only are they establishing the annulus of the disc to be the most likely source of chronic low back pain (in agreement with Nachemson and Mooney above), they are discounting the involvement other tissues as generators of the chronic symptomology.

In 2006, physician researchers from Japan published in the journal Spine the results of a sophisticated immunohistochemistry study of the sensory innervation of the human lumbar intervertebral disc (10). The article is titled:

The Degenerated Lumbar Intervertebral Disc is Innervated Primarily by Peptide-Containing Sensory Nerve Fibers in Humans

These authors note:

“Many investigators have reported the existence of sensory nerve fibers in the intervertebral discs of animals and humans, suggesting that the intervertebral disc can be a source of low back pain.”

“Both inner and outer layers of the degenerated lumbar intervertebral disc are innervated by pain sensory nerve fibers in humans.”

Pain neuron fibers are found in all human discs that have been removed because they are the source of a patient’s chronic low back pain.

The nerve fibers in the disc, found in this study, “indicates that the disc can be a source of pain sensation.”

The perspective offered by these studies from 70 years of publications and research in the best journals is that the annulus of the intervertebral disc is primarily responsible for the majority of chronic low back pain.

Above (8), Dr Vert Mooney notes in his Presidential Address to the International Society for the Study of the Lumbar Spine that, “basic studies and clinical experience suggest that mechanical therapy is the most rational approach to relief of this painful [intervertebral disc] condition.” In support of Dr. Mooney’s perspective, four such studies are reviewed here:

In 1985, Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis, a Professor Emeritus of Orthopedics and director of the Low-Back Pain Clinic at the University Hospital, Saskatoon, Canada, published an article in the journal Canadian Family Physician (11). In this study, the authors present the results of a prospective observational study of spinal manipulation in 283 patients with chronic low back and leg pain. All 283 patients in this study had failed prior conservative and/or operative treatment, and they were all totally disabled. These patients were given a “two or three week regimen of daily spinal manipulations by an experienced chiropractor.”

These authors considered a good result from manipulation to be:

“Symptom-free with no restrictions for work or other activities.”

OR

“Mild intermittent pain with no restrictions for work or other activities.”

81% of the patients with referred pain syndromes subsequent to joint dysfunctions achieved the “good” result. The reader is reminded that Drs. Inman and Saunders (2) established in 1947 that the disc itself is a source of sclerogenic pain referral.

48% of the patients with nerve compression syndromes, primarily subsequent to disc herination and/or central canal spinal stenosis, achieved the “good” result.

Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis attributed this clinical outcome to Melzack and Wall’s 1965 “Gate Theory of Pain.” He noted that the manipulation improved motion, which improved proprioceptive neurological input into the central nervous system, which in turn blocked pain. Dr. Vert Mooney, above (8), adds that the improved motion also improves the biochemistry of the disc, reducing irritation to the disc nociceptors. Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis concluded:

“The physician who makes use of this [manipulation] resource will provide relief for many back pain patients.”

In 1990, Dr. TW Meade and colleagues published the results of a randomized comparison of chiropractic and hospital outpatient treatment in the management of low back pain. This trial involved 741 patients and was published in the prestigious British Medical Journal (12). It was titled:

Low back pain of mechanical origin:

Randomized comparison of chiropractic and hospital outpatient treatment

The patients in this studied were followed for a period between 1 – 3 years. Nearly all of the chiropractic management involved traditional joint manipulation. Key points presented in this article include:

“Chiropractic treatment was more effective than hospital outpatient management, mainly for patients with chronic or severe back pain.”

“There is, therefore, economic support for use of chiropractic in low back pain, though the obvious clinical improvement in pain and disability attributable to chiropractic treatment is in itself an adequate reason for considering the use of chiropractic.”

“Chiropractic was particularly effective in those with fairly intractable pain-that is, those with a history of severe pain.”

“Patients treated by chiropractors were not only no worse off than those treated in hospital but almost certainly fared considerably better and that they maintained their improvement for at least two years.”

“The results leave little doubt that chiropractic is more effective than conventional hospital outpatient treatment.”

Importantly, the above studies indicate that the primary tissue origin of chronic back pain is the intervertebral disc. This study by Meade notes that the benefit of chiropractic is seen primarily in patients that are suffering from severe chronic pain. This would suggest that chiropractic manipulation is affecting the pain afferents arising from the disc. A plausible theory to support this is found below, at the end of this presentation.

Also, the authors of the Meade study note that if all back pain patients without manipulation contraindications were referred for chiropractic instead of hospital treatment, there would be significant annual treatment cost reductions, a significant reduction in sickness days during two years, and a significant savings in social security payments.

In 2003, the journal Spine published a randomized clinical trial involving the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory COX-2 inhibiting drugs Vioxx or Celebrex v. needle acupuncture v. chiropractic manipulation in the treatment of chronic neck and back pain (13). The title of the article is:

Chronic Spinal Pain:

A Randomized Clinical Trial Comparing Medication,

Acupuncture, and Spinal Manipulation

In this study chiropractic was better than 5 times more effective than the drugs and better than twice as effective as needle acupuncture in the treatment of chronic spine pain. Chiropractic was able to accomplish the clinical outcome without any reported adverse effects. One year after the completion of this 9-week clinical trial, 90% of the original trial participants were re-evaluated to assess their clinical status. The authors discovered that only those who received chiropractic during the initial randomization benefited from a long-term stable clinical outcome. The results of the second assessment were published in 2005 (14).

The most recent, comprehensive, and authoritative Clinical Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Low Back Pain were published in the October 2007 issue of the journal Annals of Internal Medicine. An extensive panel of qualified experts constructed these clinical practice guidelines after a review of the literature on the topic and then grading the validity of each study. The literature search for this guideline included studies from MEDLINE (1966 through November 2006), the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, and EMBASE. This project was commissioned as a joint effort of the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society. The results were presented in these publications (15, 16):

Diagnosis and Treatment of Low Back Pain: A Joint Clinical Practice Guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society

Annals of Internal Medicine

October 2007, Volume 147, Number 7, pp. 478-491

AND

Nonpharmacologic Therapies for Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain:

A Review of the Evidence for an American Pain Society

And American College of Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline

Annals of Internal Medicine

October 2007, Volume 147, Number 7, pp. 492-504

Both of these publications advocate the utilization of spinal manipulation in the management of chronic low back pain.

A relevant question is:

How does joint manipulation reduce chronic back pain arising from the intervertebral Disc?

I believe that a plausible explanation is offered by Canadian orthopedic surgeon WH Kirkaldy-Willis in the first edition (1983) of his book titled Managing Low Back Pain. Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis describes the biomechanics of how the two facet joints form a three-joint complex with the intervertebral disc. He notes that “motion at one site must reflect motion at the other two.” It is probable that spinal manipulation primarily mechanically affects the facet articulations. According to Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis, such facet motion would necessarily cause motion in the intervertebral disc. Consistent with the articles noted above, this would improve fluid mechanics of the disc, disperse the accumulation of inflammatory exudates, and initiate a neurological sequence of events that would “close the pain gait.” Regardless, the outcomes of the clinical trials noted above speak for themselves.

•••••

Can a motor vehicle collision cause low back pain?

In 1990, orthopedic surgeons Martin Gargan and Gordon Bannister published a study in the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (British) titled (18):

Long-Term Prognosis of Soft-Tissue Injuries of the Neck

In this study they found that 42% of whiplash-injured patients suffer from chronic low back pain 10.8 years following their initial injury. As noted above, the chronic low back pain noted by these researchers is probably discogenic and sclerotogenous; this means that the patient is probably not suffering from compressive neuropathology.

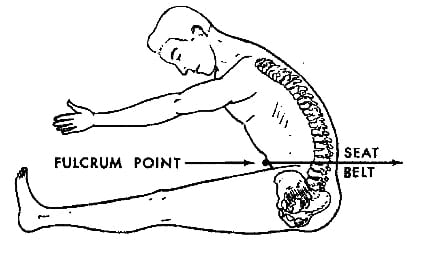

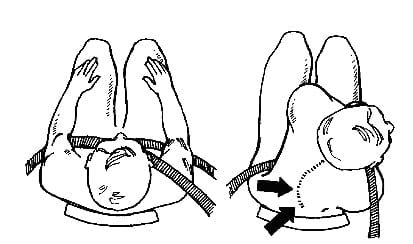

Over the decades, several authors have proposed a mechanism for the observed disc and other deep spinal tissue trauma occurring as a consequence of a motor vehicle collision (19, 20, 21, 22). These mechanisms primarily involve a fulcrum-type stress of the lumbar or lower thoracic spine, in flexion, around the lap belt (20):

The addition of a shoulder harness to the lap belt introduces a flexion and rotational component to the trauma (22). This type of mechanism is notorious for injuring the lumbar intervertebral disc:

SUMMARY POINTS

- The intervertebral disc is innervated with nociceptors.

- The intervertebral disc itself, in the absence of compressive radiculopathy, is capable of producing low back and leg pain.

- The intervertebral disc is probably the most frequent source of chronic low back pain.

- The referred pain from disc injury is diffuse, non-specific, and can cause lower extremity pain. This pain has been known as “sclerotogenous” pain for more than 60 years.

- Sclerotogenous pain does not follow a myotomal or dermatomal pattern.

- Motor vehicle collisions can injure the low back discs and other deep structures. These injuries are often the consequence of seat belt fulcrum stress.

- Many studies have shown that chiropractic spinal adjusting is safe and effective in treating discogenic low back pain and it concomitant sclerotogenous referred pain.

References

1) Mixter WJ, Barr JS; Rupture of the intervertebral disc with involvement of the spinal canal; New England Journal of Medicine; 211 (1934), pp. 210–215.

2) Inman VT, and Saunders JMB, Anatamico-physiological aspects of injuries to the intervertebral disc, J Bone Joint Surg 29 (1947), pp. 461–468.

3) Nachemson, AL, Spine, Volume 1, Number 1, March 1976, pp. 59-71.

4) Smyth MJ, Wright V, Sciatica and the intervertebral disc. An experimental study. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery [American]; Vol. 40, No. 6. December 1958, pp. 1401-1418.

5) Jayson M, Editor; The Lumbar Spine and Back Pain, Third Edition, Churchill Livingstone, 1987, p. 60.

6) Bogduk N, Tynan W, Wilson AS, The nerve supply to the human lumbar intervertebral discs, Journal of Anatomy; 1981, 132, 1, pp. 39-56.

7) Bogduk N, The innervation of the lumbar spine; Spine. April 1983;8(3): pp. 286-93.

8) Mooney, V, Where Is the Pain Coming From? Spine, 12(8), 1987, pp. 754-759.

9) Kuslich S, Ulstrom C, Michael C; The Tissue Origin of Low Back Pain and Sciatica: A Report of Pain Response to Tissue Stimulation During Operations on the Lumbar Spine Using Local Anesthesia; Orthopedic Clinics of North America, Vol. 22, No. 2, April 1991, pp.181-7,

10) Ozawa, Tomoyuki MD; Ohtori, Seiji MD; Inoue, Gen MD; Aoki, Yasuchika MD; Moriya, Hideshige MD; Takahashi, Kazuhisa MD; The Degenerated Lumbar Intervertebral Disc is Innervated Primarily by Peptide-Containing Sensory Nerve Fibers in Humans; Spine, Volume 31(21), October 1, 2006, pp. 2418-2422.

11) Kirkaldy-Willis WH, Cassidy JD; Spinal Manipulation in the Treatment of Low Back Pain; Canadian Family Physician, March 1985, Vol. 31, pp. 535-540

12) Meade TW, Dyer S, Browne W, Townsend J, Frank OA; Low back pain of mechanical origin: Randomized comparison of chiropractic and hospital outpatient treatment; British Medical Journal; Volume 300, June 2, 1990, pp. 1431-7.

13) Giles LGF, Muller R; Chronic Spinal Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial Comparing Medication, Acupuncture, and Spinal Manipulation; Spine, July 15, 2003; 28(14):1490-1502.

14) Muller R, Lynton G.F. Giles LGF, DC, PhD; Long-Term Follow-up of a Randomized Clinical Trial Assessing the Efficacy of Medication, Acupuncture, and Spinal Manipulation for Chronic Mechanical Spinal Pain Syndromes; Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics, January 2005, Volume 28, No. 1.

15) Roger Chou, MD; Amir Qaseem, MD, PhD, MHA; Vincenza Snow, MD; Donald Casey, MD, MPH, MBA; J. Thomas Cross Jr., MD, MPH; Paul Shekelle, MD, PhD; and Douglas K. Owens, MD, MS; Diagnosis and Treatment of Low Back Pain; Annals of Internal Medicine; Volume 147, Number 7, October 2007, pp. 478-491.

16) Roger Chou, MD, and Laurie Hoyt Huffman, MS; Nonpharmacologic Therapies for Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain; Annals of Internal Medicine; October 2007, Volume 147, Number 7, pp. 492-504.

17) Kirkaldy-Willis WH, Managing Low Back Pain, Churchill Livingstone, 1983, p. 19.

18) Gargan MF, Bannister GC; Long-Term Prognosis of Soft-Tissue Injuries of the Neck; Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (British); Vol. 72-B, No. 5, September 1990, pp. 901-3.

19) Chance GQ; Note on a type of flexion fracture of the spine; British Journal of Radiology; September 1948, No. 21, pp. 452-453.

20) Howland WJ, Curry JL, Buffington CB. Fulcrum fractures of the lumbar spine. JAMA. 1965 Jul 19;193:240-1.

21) Rennie W, Mitchell N. Flexion distraction fractures of the thoracolumbar spine. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1973 Mar;55(2):386-90.

22) Murphy DJ; “Children in Motor Vehicle Collisions”, in Pediatric Chiropractic, Edited by Anrig C and Plaugher G; Williams & Wilkins, 1998.