Kim was only nineteen years of age, yet she had already experienced three significant motor vehicle collisions, and in each she suffered injuries. Her injuries were always painful, but never debilitating; there were no fractures, dislocations, radiculopathies, myelopathies, or instabilities. After each collision she was medically evaluated, but there were no radiographs or other types of imaging. Her diagnosis for each was “soft tissue injury” or a “sprain-strain” type of injury. Her treatment was rest, soft collar, heat-pack and pain analgesics. After each injury, she seemed to slowly improve following this management advice.

About six months after her last injury, Kim was symptomatically much improved but not yet resolved; then she suffered something new and excruciating. While showering, she turned her head to the left to grab the shampoo which initiated a sharp, lightning-bolt sensation in the left side of her neck. After the initial shot of pain, her neck became very stiff and appeared to go into some sort of spasm. There was a lot of pain in her neck and her neck movements were greatly reduced.

That night Kim’s neck was still very painful and she could not move her neck. In bed she was unable to get comfortable which disturbed her sleep. The next day she was still unimproved, and she once again decided to go to her doctor.

Kim’s doctor observed a significant right antalgic lean of her cervical spine with significant spasms of her cervical muscles. However, deep tendon reflexes, upper extremity myotomal strength, and upper extremity superficial sensation with pinwheel and light touch were all normal. Once again, no imaging was performed. None-the-less, Kim’s doctor diagnosed her condition as a “pinched nerve” causing muscle spasms. He prescribed muscle relaxers, analgesics, and a white-colored soft cervical collar.

For the next six weeks, Kim dutifully took her medicines and wore her cervical collar. Yet, she did not appear to be improving. Her neck remained very painful, stiff, and bent at a funny angle. She was finding it nearly impossible to attend her college classes and complete the required assignments. Her sleep was also so poor that she was suffering from sleep deprivation fatigue. Now desperate, Kim decided to see a chiropractor.

Kim’s chiropractor’s was young, having graduated from school only the year before. His examination also found no problems with strength, sensation, or deep tendon reflexes in the upper or lower extremities. The chiropractor exposed radiographs, and the chief finding was a significant right antalgic lean, consistent with her postural presentation. Happily, the x-rays showed no fractures, degenerative disease, ligamentous instabilities, or any other type of acquired or developmental pathology.

The chiropractor recommended a treatment of an adjustment “to straighten out the antalgic lean.” Because Kim’s cervical spine was leaning to the right (a right antalgic lean), the adjustment was designed to contact the cervical spine on the left side at the C4 vertebra level (as C4 was the apex of the antalgic lean) while simultaneously contacting the head on the right side; a force was then delivered to the left side of the neck while bringing the head back from right to left; a left sided cervical spine adjustment. It made sense. It seemed logical. Somehow the spine had become stuck, and the adjustment on the left side would straighten it out.

Kim screamed, loudly, several times. The volume scared the young chiropractor and several of his other patients who were in the office. Kim cried a little because the adjustment hurt very much. It would have been worth it if it would had fixed her problem. But it did not. In fact she felt worse; there was more pain, more spasm, and her neck appeared to be more bent to the right. Her chiropractor did not know what to say or do.

The next day, Kim’s predicament was unchanged. A week later she was still unchanged, and now desperate. School and work were all but impossible. Both medical and chiropractic had failed to help her. She did not know where to next turn. Her next advice came unsolicited.

Fatigue and pain had taken its toll on Kim’s appearance; she looked awful for her mere nineteen years of age. A middle-aged woman at the cosmetics counter of a mall anchor store, while assisting Kim with products, inquired about her obvious neck condition (Kim was still wearing her cervical collar). Her recommendation was for Kim to see her chiropractor. In the conversation, Kim shared how her prior chiropractic experience did not help her and actually seemed to make her worse. The woman behind the cosmetic counter assured Kim that her chiropractor was different, smart, experienced, and the best. There was something about the cosmetic counter woman’s voice, mannerisms, and convictions. Desperate, Kim decided to consult the second chiropractor……….

•••••

The most recent comprehensive review of the Synovial Fold Entrapment Syndrome is written by Alexandra Webb and colleagues and will be published in the April 2011 issue of the journal Manual Therapy (Epub at this time, 2/15/11) (1).

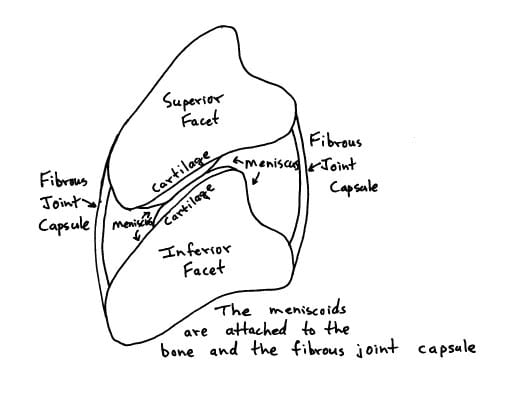

In this article, Dr. Webb and colleagues note that intra-articular synovial folds are formed by folds of synovial membrane that project into the joint cavity. Cervical spine synovial folds extend 1–5 mm between the articular surfaces. Synovial folds are found in synovial articulations throughout the vertebral column. Synovial folds in the vertebral column were first documented in 1855.

Dr. Webb and colleagues note that the published literature uses a number of names to identify these synovial folds, including:

- “Synovial fold is the most accurate name to apply to these structures.”

- Meniscus / Menisci

- Meniscoid

- Intra-articular inclusions

- Intra-articular discs

Anatomically, synovial folds contain an abundant vascular network and sensory nerve fibers (1).

The entrapment hypothesis is usually proposed to explain the clinical presentations of the synovial fold syndrome. “An abnormal joint movement may cause a synovial fold to move from its normal position at the articular margins to become imprisoned between the articular cartilage surfaces causing pain and articular hypomobility accompanied by reflex muscle spasm (1).”

“Synovial fold entrapment has been used to explain the pathophysiology of torticollis and the relief of pain and disability following spinal manipulation.” The traction forces generated during manipulation would cause release of a trapped fibro-adipose synovial fold from between the articular surfaces (1).

Additionally, contusions, rupture and displacement of the synovial folds have been reported at autopsy following fatal motor vehicle trauma; these injuries are not visible at post-mortem using conventional X-ray, CT or MRI (1).

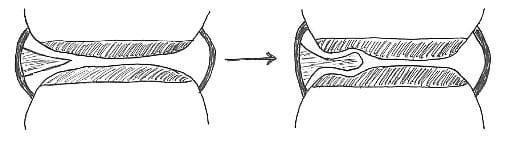

With repeated mechanical impingement between the articular surfaces, the synovial fold may differentiate into fibrous tissue to varying degrees. The fibrous apex of the synovial indents the articular hyaline cartilage, further entrapping the apex of the synovial fold. Manipulative therapy may traction and separate the articular surfaces apart, releasing the entrapped synovial fold. (Drawing below based on #1).

Historically, the entrapped synovial fold syndrome has been written about for decades. In the 1971 translation of their authoritative reference text The Human Spine in Health and Disease, Drs. Schmorl and Junghanns note (2):

“Like other body articulations, the apophyseal joints are endowed with articular capsules, reinforcing ligaments and menisci-like internal articular discs.”

“Like any other joint, the motor segment may become locked. This is usually associated with pain.” Chiropractors refer to such events as subluxations. These motor unit disturbances can cause torticollis and lumbago.

“Various processes may cause such ‘vertebral locking.’ It may happen during normal movement. The incarceration of an articular villus or of a meniscus in an apophyseal joint may produce locking.”

If a joint is suddenly incarcerated within the range of its physiologic mobility, as occurs with the meniscus incarceration of the knee joint, it is an “articular locking or a fixed articular block.”

“Such articular locking is also possible in the spinal articulations (apophyseal joints, intervertebral discs, skull articulations, lumbosacral articulations). They may be mobilized again by specific therapeutic methods (stretchings, repositioning, exercises, etc.). Despite many opinions to the contrary, this type of locking is today increasingly recognized by physicians. Many physicians are employing manipulations which during the past decades were the tools of lay therapists only (chiropractors, osteopaths). However, these methods have at times been recommended by physicians. They have also been known in folk medicine and in medical schools of antiquity.”

Schmorl and Junghanns’ text includes two photographs of anatomical sections through the facet joints showing these “menisci-like internal articular discs,” or meniscus. They also included three radiographs and one drawing showing abnormal gapping of an articulation as a consequence of meniscus entrapment in a facetal articulation. They note that such a meniscoid incarceration can cause acute torticollis, and they show a “follow-up roentgenogram after manual repositioning” resulting in “immediate relief of complaints and complete mobility.”

In 1985, 30 distinguished international multidisciplinary experts collaborated on a text titled Aspects of Manipulative Therapy (3). The comments in this text pertaining to the interarticular meniscus (synovial entrapment syndrome) include:

“Histologically, meniscoids are synovial tissue.”

“Their innervation is derived from that of the capsule.”

The current hypothetical model of the mechanism involved in acute joint locking is based on a phenomenon in which the “meniscoid embeds itself, thereby impeding mobility.”

“It is highly probable that the meniscoids do play an important role in acute joint locking, and this is confirmed by the observation that all the joints afflicted by this condition are equipped with such structures.”

In 1986, physical therapist Gregory Grieve authored a text titled Modern Manual Therapy of the Vertebral Column (4). This text boasts 61 international multidisciplinary contributors, contains 85 topic chapters, and is 898 pages in length. In the chapter titled “Acute Locking of the Cervical Spine” the text notes that a cause of acute cervical joint locking includes:

“Postulated mechanical derangements of the apophyseal joint include nipped or trapped synovial fringes, villi or meniscoids.”

In her 1994 text Physical Therapy of the Cervical and Thoracic Spine, professor of physiotherapy from the University of South Australia, Ruth Grant writes (5):

“Acute locking can occur at any intervertebral level, but is most frequent at C2-C3. Classically, locking follows an unguarded movement of the neck, with instant pain over the articular pillar and an antalgic posture of lateral flexion to the opposite side and slight flexion, which the patient is unable to correct. Locking is more frequent in children and young adults. In many, the joint pain settles within 24 hours without requiring treatment (because the joint was merely sprained or because it unlocked spontaneously), but other patients will require a localized manipulation to unlock the joint.”

In his 2004 text titled The Illustrated Guide to Functional Anatomy of the Musculoskeletal System (6), renowned physician and author Rene Cailliet, MD comments on the anatomy of the interarticular meniscus, stating:

“The uneven surfaces between the zygapophyseal processes are filled by an infolding of the joint capsule, which is filled with connective tissue and fat called meniscoids. These meniscoids are highly vascular and well innervated.”

In the fourth edition of his textbook Clinical Anatomy of the Lumbar Spine and Sacrum (7), physician, anatomist, and researcher Dr. Nikolai Bogduk writes:

“The largest of the meniscoid structures are the fibro-adipose meniscoids. These project from the inner surface of the superior and inferior capsules. They consist of a leaf-like fold of synovium which encloses fat, collagen and some blood vessels.”

“Fibro-adipose meniscoids are long and project up to 5 mm into he joint cavity.”

“A relatively common clinical syndrome is ‘acute locked back.’ In this condition, the patient, having bent forward, is unable to straighten because of severe focal pain on attempted extension.”

“Maintaining flexion is comfortable for the patient because that movement disengages the meniscoid. Treatment by manipulation becomes logical.”

The January 15, 2007 publication of the top ranked orthopaedic journal Spine contains an article titled (8):

High-Field Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Meniscoids

in the Zygapophyseal Joints of the Human Cervical Spine

Key Points From this article include:

1) Pain originating from the cervical spine is a frequent condition.

2) Neck pain can be caused by pathologic conditions of meniscoids within the zygapophysial joints.

3) “Cervical zygapophysial joints are well documented as a possible source of neck pain, and it has been hypothesized that pathologic conditions related to so called meniscoids within the zygapophysial joints may lead to pain.”

4) The meniscoids of the cervical facet joints contain nociceptors and may be a source of cervical facet joint pain.

5) Proton density weighted MRI image sequence is best for the evaluation of the meniscoid anatomy and pathology.

6) Meniscoids are best visualized with high-field MRI of 3.0 T strength.

7) Meniscoids are best depicted in a sagittal slice orientation.

8) The meniscoids in C1-C2 differ from those in the rest of the cervical spine.

9) Meniscoids may become entrapped between the articular cartilages of the facet joints. This causes pain, spasm, reduced movement, and “an acute locked neck syndrome.” “Spinal adjusting can solve the problem by separating the apposed articular cartilages and releasing the trapped apex.”

Clinical Applications

Decades of evidence support the perspective that the inner aspect of the facet capsules have a process that extends into and between the facet articular surfaces. This evidence includes anatomical sections, histological sections, MR imaging, and clinical evaluations. This synovial fold can become entrapped between the facet articulating surfaces, producing pain, spasm, and antalgia. Published terminology for the anatomy includes synovial fold, synovial villus, meniscoid, meniscoid block, and joint locking.

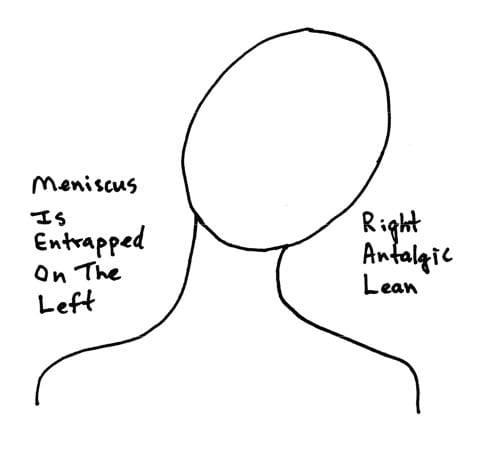

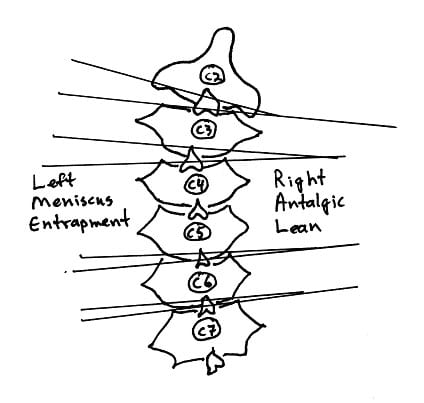

Using the cervical spine as a representative model, a classic clinical presentation would be that of an acute torticollis. If the synovial fold is entrapped on the left side of the cervical spine, the patient would present with an antalgia of right lateral flexion; in other words, the patient bends away from the side of entrapment. The patient’s primary pain symptoms will be on the side of entrapment, in this example, the left side (exactly like our patient Kim). Active range of motion examination will show that the patient is capable of additional lateral flexion to the right, but will not laterally flex to the left because of increased pain; once again this is because the synovial fold is entrapped on the left side and left lateral flexion increases meniscus compression, pain, and spasm. This is also why the patient is antalgic to the right; such positioning reduces left sided synovial fold compression, pain, and spasm.

Additional clinical evaluation will reveal no sings of radiculopathy; no alterations of superficial sensation in a dermatomal pattern, and no signs of motor weakness or altered deep tendon reflexes. An important clinical feature is that although the patient will not laterally flex the cervical spine to the left because of increased pain and spasm, left cervical lateral flexion against resistance without motion (the doctor holds the patient’s head so that there is no motion even though the left-sided cervical muscles are contracting) will not increase the patient’s pain. This is because the involvement is not muscular. Muscle contraction against resistance will not increase pain as long as the joint does not move in the meniscoid block syndrome.

Additional clinical evaluation will reveal no sings of radiculopathy; no alterations of superficial sensation in a dermatomal pattern, and no signs of motor weakness or altered deep tendon reflexes. An important clinical feature is that although the patient will not laterally flex the cervical spine to the left because of increased pain and spasm, left cervical lateral flexion against resistance without motion (the doctor holds the patient’s head so that there is no motion even though the left-sided cervical muscles are contracting) will not increase the patient’s pain. This is because the involvement is not muscular. Muscle contraction against resistance will not increase pain as long as the joint does not move in the meniscoid block syndrome.

A typical treatment protocol to manage the synovial fold entrapment syndrome is that the patient is manipulated in an effort to free the entrapped meniscus. Post-graduate teachings in chiropractic orthopedics (Richard Stonebrink, DC, DABCO) and clinical experience indicate that the most successful manipulation would induce additional right lateral flexion; in other words, the manipulation would cause further right side antalgia. Such a maneuver would cause both a gapping of the facets on the left side as well as a tensioning of the left side facet capsules, together pulling free the entrapped synovial fold. When the precise level of synovial fold entrapment is ascertained and that precise level is manipulated in the appropriate direction to cause the intended neurobiomechanical changes, it is referred to by chiropractors as a “spinal adjustment.” The depth and speed of such an adjustment must be sufficient to overcome local muscle spasms that reflexively exist as a consequence of the pain the patient is experiencing. Following this first manipulation/adjustment, the patient may benefit from 10-15 minutes of axial traction to the cervical spine. Experience suggests that most patients will benefit from the application of a soft cervical collar, worn continuously until the following day. The patient is evaluated and manipulated/adjusted again the second day, followed once again by optional axial cervical traction, but there is no need for the soft cervical collar on the second day. The patient is given the third day off, returning the fourth day for a final evaluation and adjustment/manipulation. It is typical for complete symptomatic resolution to occur in a period of 3 – 5 days following onset and treatment.

An important caution in adjusting/manipulating the meniscoid block lesion is to not do so in such a manner that it straightens the right antalgic lean. Recall that the patient is antalgic to the right because the synovial fold is entrapped on the left side. To attempt to straighten the right antalgic lean out will increase the meniscoid compression, pain and spasm, making the patient truly unhappy. In contrast, the adjustment/manipulation should be made in such a manner that the right antalgic lean is enhanced, gapping the left sided articulations, freeing the entrapped synovial fold, reducing pain and spasm.

As described in the eighth edition of his book (1982) Textbook of Orthopaedic Medicine (9), orthopaedic surgeon Sir James Cyriax describes how the fibers of the multifidus muscles blend with the facet joint capsular fibers. Chiropractic orthopedic training indicates that at the beginning of any joint movement, appropriate local articular proprioception will quickly initiate a contraction of the multifidus muscle, tightening the capsular ligaments, and pulling the meniscus of that joint into such a position that it cannot become entrapped. This suggests that the etiology of the meniscoid block syndrome is a failure of appropriate proprioceptive driven reflexes, indicative of a long-standing biomechanical problem. It is reasonable and appropriate to treat the long-standing biomechanical problem with a more prolonged series of spinal adjustments/manipulations and indicated rehabilitation. Failure to do so often results in frequent reoccurrences of the synovial fold entrapment syndrome following trivial mechanical environmental stresses.

•••••

…It had been eight weeks since the incidence in the shower. Kim’s white cervical collar had turned brown because she was wearing it constantly, day and night.

The examination with the second chiropractor showed that Kim’s condition was unchanged; right cervical spine and head antalgic lean, almost no range of motion, and significant associated spasm. Yet, deep tendon reflexes, superficial sensation, and myotomal strength were all normal. There were no pathological reflexes suggestive of an upper motor neuron lesion. There were no indications of infection or autoimmune issues.

New cervical radiographs were exposed, and as before there were no signs of degeneration, fracture, congenital or acquired anomalies. Certainly, there were no findings that could account for Kim’s antalgia, pain, and spasm.

But there were some subtle hints giving clues to the pathology, diagnosis, and treatment, as noted above. The second chiropractor had learned about the syndrome and presentation in post-graduate education, and he had seen a number of patients with similar presentations over the years. Those subtle hints included:

- The antalgic lean was to the right side, by about 35 degrees.

- Kim would isolate the region of greatest pain as being on the left side, at approximately the C4-C5 level.

- Kim could voluntarily laterally flex her cervical spine further to the right, by about 5 degrees, effectively worsening the right antalgic lean.

- Kim was unable to laterally flex her cervical spine to the left at all; to attempt to do so was far too painful.

- Kim sat up at the end of the table. The chiropractor stood at her right side, facing her, and placed his hands on the left side of Kim’s head. Kim was instructed to laterally flex her head/neck to the left, into the chiropractor’s hands. As Kim did this, the chiropractor used enough resistance with his hands to prevent all motion to the left. The left sided cervical musculature contracted nicely, and there was no increased pain as long as the chiropractor prevented all left sided motion. THERE WAS NO PAIN ON RESISTIVE EFFORTS to the left, as long as it was isometric and not allowing any motion.

SUMMARY

- Two sets of normal radiographs suggest that Kim is not suffering from fracture, dislocation, degenerative disease, acquired or congenital anomalies.

- There were no indications of infection or autoimmune issues.

- Normal deep tendon reflexes, superficial sensation and myotomal strength in both upper and lower extremities make it improbable that Kim is suffering from radiculopathy, neuropathy, or myelopathy.

- No increased pain with isometric contraction of the muscles on the contra-lateral side of the antalgic lean (the left side in this case); as long as motion was prevented, contracting the muscles did not increase the pain. This indicates that the problem is not in the muscle.

- A marked increase of pain with any left lateral flexion motion, whether active or passive.

- Kim has a history of three injurious motor vehicle collisions where she injured her cervical spine.

- Kim’s current problem began with a single motion of her neck to the left side.

- Time and analgesics did not improve Kim’s symptoms or signs.

- A left sided cervical spine chiropractic adjustment designed to straighten out her right antalgic lean caused an acute exacerbation of her symptoms and worsened her condition.

INTERPRETATION

Kim has a left-sided synovial joint entrapment, probably at the C4-C5 facet, causing an acute joint locking. Kim is antalgic to the right because such positioning reduces pressure on the left sided synovial entrapment. In contrast, any left lateral flexion increases the pinch and associated pain on the entrapped synovial fold. The cervical muscles are in spasm as a consequence of the antalgia and pain.

TREATMENT

The second chiropractor convinced Kim that the only solution for her problem was to manually adjust the right cervical spine in lateral flexion at the C4-C5 articulation level. This adjustment is designed to make the antalgic lean worse; remember, Kim could slightly laterally flex her cervical spine to the right without aggravating her pain. The adjustment would have to have enough velocity and depth to overcome the resistance of the increased tone from the spasmed musculature. If the adjustment was successful, it would gap the left sided C4-C5 facetal articulation, freeing the entrapped synovial fold. If successful, Kim should notice 50-80% improvement in antalgia, pain, and motion, essentially instantaneously.

RESULTS

As expected, success, with a single adjustment. Kim was about 75% improved within minutes. Although the adjustment was designed to make her right antalgic lean worse, after the cavitation of the C4-C5 articulation on the left and freeing-up of the entrapped synovial fold, Kim was significantly straighter, less antalgic.

FOLLOW-UP

Kim and other such patients should be adjusted in a similar fashion the very next day, as noted above. Typically, there is no adjustment the third day, but the patient is once again adjusted the fourth day. Residual muscle hypertonicity and joint stiffness should be resolved within 3-5 days.

Eight weeks in a cervical collar necessitates muscular rehabilitation, starting with isometirc resistive efforts and gradually proceeding to isotonic resistive efforts.

As noted above, a proposed root cause of the acute locked neck secondary to synovial fold entrapment is a post-traumatic mismatch between joint motion and the mechanoreceptive reflex to the shunt muscle that contracts the multifidi; When functioning appropriately, multifidi contraction would tighten the capsule and move the synovial fold out of harm’s way. This means the synovial fold entrapment exists secondary to a post-traumatic disruption of the proprioceptive driven reflex. The retraining of this proprioceptive mismatch may require a series of adjustments and exercises delivered over a period of time.

I was the second chiropractor.

And for a number of years, I counted the patients referred to me either directly or indirectly from the woman at the mall anchor store cosmetics counter. I stopped counting at about 700.

Dan Murphy, DC

References

1) Webb AL, Collins P, Rassoulian H, Mitchell BS; Synovial folds – A pain in the neck?; Manual Therapy; April 2011; Vol. 16; No. 2; pp. 118-124.

2) Junghanns H; Schmorl’s and Junghanns’ The Human Spine in Health and Disease; Grune & Stratton; 1971.

3) Idczak GD; Aspects of Manipulative Therapy; Churchill Livingstone; 1985.

4) Grieve G; Modern Manual Therapy of the Vertebral Column; Churchill Livingstone; 1986.

5) Grant R; Physical Therapy of the Cervical and Thoracic Spine, second edition; Churchill Livingstone, 1994.

6) Cailliet R; The Illustrated Guide to Functional Anatomy of the Musculoskeletal System, American Medical Association, 2004.

7) Bogduk N; Clinical Anatomy of the Lumbar Spine and Sacrum, fourth edition; Elsevier, 2005.

8) Friedrich KM. MD, Trattnig S, Millington SA, Friedrich M, Groschmidt K, Pretterklieber ML; High-Field Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Meniscoids in the Zygapophyseal Joints of the Human Cervical Spine; Spine; January 15, 2007, Volume 32(2), January 15, 2007, pp. 244-248.

9) Cyriax J; Textbook of Orthopaedic Medicine, Diagnosis of Soft Tissue Lesions, eighth edition; Bailliere Tindall, 1982.