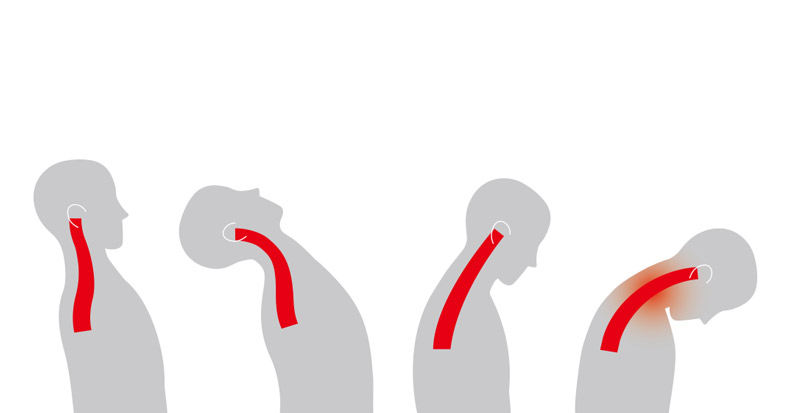

Because rear-end motor vehicle collisions are the most common cause of whiplash injury, researchers have continuously sought to better understand this unique injury process, not only to derive more effective treatment strategies, but also to implement safety mechanisms in automobiles to reduce the risk of injury in the event of a car accident. As such, investigators have identified four phases of injury potential during the rapid acceleration and deceleration of the head and neck: retraction, extension, rebound, and protraction.

- RETRACTION PHASE: Immediately after impact, the upper torso is pushed forward by the seat back while the occupant’s head remains relatively stationary, creating head retraction similar to tucking in the chin. This produces an S-shape of the cervical spine in which the upper cervical segments flex while the lower cervical segments extend. Maximal retraction may occur at or near the point of head restraint contact (depending on headrest position). A primary injury mechanism believed to be associated with this phase is a rapid pressure spike within the spinal canal caused by the sudden differential motion between the upper and lower cervical spine.

- EXTENSION PHASE: This phase occurs immediately after the head reaches maximum retraction, sometimes even before striking the headrest, causing the occupant’s head to extend rearward as if looking upward. This places the entire cervical spine into extension. Excessive extension can also occur when no headrest is present or when the headrest is positioned too low or too far behind the occupant’s head, contributing to a hyperextension mechanism of injury.

- REBOUND PHASE: Here, the occupant’s head reverses direction after reaching peak extension and rebounds forward. This rebound action produces some of the highest axial and shear forces measured in whiplash testing, making the cervical spine particularly vulnerable to excessive flexion forces.

- PROTRACTION PHASE: Injury can occur after rebound when the differential motion between the head and torso is reversed—for example, when the seatbelt and shoulder harness restrain the upper torso while the head continues its forward motion. Similar to the transition from the S-shaped curve into full extension during the retraction-to-extension phase, the cervical spine here rapidly shifts into flexion, producing another pressure spike within the spinal canal like that observed during a front-end impact.

It’s important to note that this entire process occurs within 50–80 milliseconds, roughly three to four times faster than it would take for visual input from the eyes to reach the brain and for the brain to process the information and send signals to the neck muscles to activate in an attempt to brace against injury. As such, strategies employed before a collision can help protect the head and neck from injury. Experts advise positioning the headrest so that its top is at least level with the top of the head and maintaining a distance of less than two inches (five centimeters) between the back of the head and the headrest. Studies also support keeping the seat back at an angle between 100 and 110 degrees to prevent the body from sliding upward during a collision, which can place the head higher than the headrest. Of course, always wear your seatbelt. In the event of a rear-end collision, clinical guidelines consistently identify chiropractic care as an effective conservative treatment option for reducing pain and disability.