Barbara is a 45-year old woman with two adult children. She is employed full-time as a sales clerk at the local mall. Her job is not physically demanding nor is it ergonomically challenging. Her job allows her to assume multiple physical positions throughout the day while she is assisting a variety of customers with a variety of needs. There is no required heavy lifting or prolonged postures.

Barbara is fit, with good muscle tone and posture. She stands 5 feet 4 inches tall and weight 120 pounds. Her exercise regime consists of walking several miles per day, nearly every day of the week, with a group of her friends.

Barbara has suffered with chronic headaches for 24 years. In addition, her headaches seemed to make her right shoulder ache.

Barbara’s headaches began when she was involved in a motor vehicle collision that occurred at 21 years of age. She did not recall many of the details of the collision other than that she was the driver of a vehicle that was struck from the rear. The collision caught her by surprise and she remembers her head being thrown backwards. There was no loss of consciousness, and she did not experience being dazed, confusion, disorientation, or loss of any memory. The damage to her vehicle was minor, and she was able to drive away from the accident scene after exchanging insurance information with the man who was driving the striking vehicle.

Barbara did not experience pain or any other complaints at the accident scene. However, as the day progressed, she became aware of some minor neck stiffness. The next day was a different story. Barbara recalls that the next morning she was unable to pick her head up off her pillow without using her hands to assist her. Her neck was painful and stiff. And, she had a headache.

Barbara attributed her neck and head signs and symptoms to a “strain” injury caused by the vehicle collision she was involved in. She took some over-the-counter pain pills, and within a few days she was much improved.

However, about a week after the collision, Barbara became more aware that she still had a headache, and that it did not appear to be improving. Rather it seemed to be becoming more pronounced. The headache was located at the right upper posterior area of her neck and also around and behind her right eye.

Since being injured 24 years ago, Barbara has had to constantly deal with her headaches. They occur frequently and range in severity from annoying to debilitating. When she is suffering from a bad headache, she also notices an abnormal sensitivity to bright lights (photophobia). She notes that apparent triggers for her headaches range from certain neck movements to prolonged neck postures. Her headaches are always only on her right side.

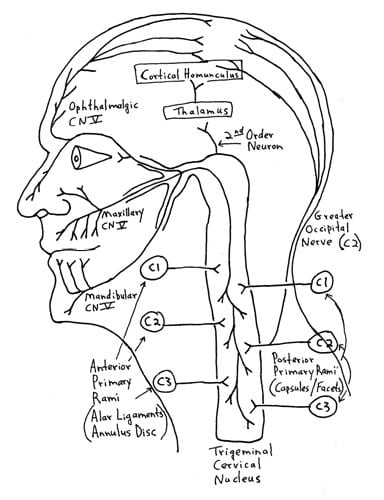

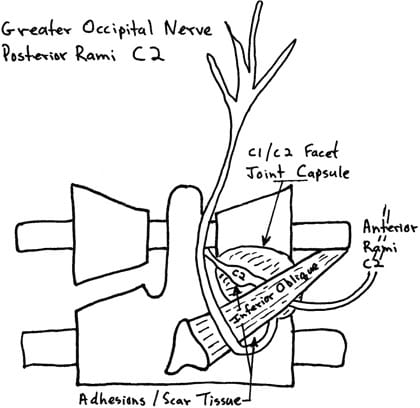

Barbara’s examination shows significantly reduced lateral flexion and rotation of the upper cervical spine on the right side. She is very sensitive to mild/moderate digital pressure applied to the suboccipital region and muscles. Importantly, her right-sided frontal (around her eye) headache can be triggered by sustained deeper pressure at the inferior margin of the right inferior oblique muscle. Recall, the inferior oblique muscle exists between the spinous process of the axis (C2) and the transverse process of the atlas (C1). (Two easily identifiable landmarks for a practicing chiropractor; see drawing page 10).

Barbara reports that she has consulted a number of medical doctors (general practitioners, not specialists) about these headaches, resulting in her taking a variety of over-the-counter and/or prescription medications. She reports that these drugs definitely help her, especially when her headache is severe. She states that she takes pain medicines for her headache 10-15 days per month. But, after developing some gastrointestinal bleeding from taking over-the-counter drugs, her primary care physician suggested she try the COX-2 inhibitor drug Celebrex. She has now been consuming Celebrex 10-15 days per month, reporting that it is quite helpful when she has a bad headache.

However, Barbara became concerned after hearing media reports of Celebrex and other pain medicines being associated with an increased risk of heart attacks. In addition, she reported that she was weary of having to consume pain medicines 10-15 days per month to function appropriately in her life. Barbara acknowledges that medicines she had been taking for her headaches were helpful, but that they had not cured her headaches, and her suffering had been going on for 24 years.

Barbara self referred herself to our office as it was on her way home from work. She had seen no other chiropractors or physical therapists for her headaches. Our office was the first.

••••••••••

It has been written in top, respected journals, since at least the 1940s, that whiplash injury to the neck can cause chronic headaches. Whiplash injury pioneer Ruth Jackson, MD, wrote about this phenomenon as early as 1947.

Ruth Jackson, MD (1902-1994), was the world’s first female admitted into the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (1937). She began her orthopedic private practice in Dallas in 1932. From 1936 to 1941, Dr. Jackson was Chief of Orthopaedics at Parkland Hospital in Fairmont, Texas. In 1945, she had her own private clinic built in Dallas. In 1956 she published her acclaimed, authoritative book entitled TheCervicalSyndrome. The fourth and final edition of her book was published in 1978 (1). Dr. Jackson retired from clinical practice in 1989 at the age of 87 years.

In 1947, Dr. Jackson published a study in the Journal of the American Medical Women’s Association titled (2):

The Cervical Syndrome As a Cause of Migraine

In this article, Dr. Jackson notes that at least half of patients suffering from cervical syndrome will also complain of headaches as one of their principle symptoms. The cervical syndrome is caused by “cervical nerve root irritation,” and this nerve root irritation can occur as a consequence of whiplash trauma.

Dr. Jackson noted that irritation of the upper cervical spine nerve roots, C1-C2-C3, are most likely to cause headache, and that it is these upper cervical spine nerve roots that are most vulnerable to whiplash trauma. In addition, these post-traumatic headaches may still be present decades later. (Recall, Barbara’s headaches were triggered by a motor vehicle collision, and she had been suffering with headaches for 24 years).

•••••

About a decade later, in the late 1950s, the concept of chronic whiplash-generated headache was supported by the writings of Emil Seletz, MD.

Dr. Emil Seletz (1907-1999) was a neurosurgeon in Beverly Hills, California. Dr. Seletz worked at the Los Angeles General Hospital, and he was faculty at the University of California, Los Angeles, medical school. He was also chief of neurosurgery at Cedar’s Hospital (now called Cedars-Sinai Medical Hospital) in Los Angeles, and Professor of Neurological Surgery at the University of Southern California School of Medicine. By 1957, Dr. Seletz had treated more than 20,000 injury patients, and he began publishing a series of articles pertaining to whiplash trauma and headaches. These include (3, 4, 5):

Craniocerebral Injuries and the Postconcussion Syndrome

Journal of the International College of Surgeons

January 1957, Vol. 27, No. 1, pp. 46-53

Headache of Extracranial Origin

California Medicine

November 1958, Vol. 89, No. 5, pp. 314-17

Whiplash Injuries

Neurophysiological Basis for Pain and Methods Used for Rehabilitation

Journal of the American Medical Association

November 29, 1958, pp. 1750-1755

In these articles, Dr. Seletz stressed that the cervical spine causes headaches because of a neuroanatomical relationship between the 2nd cervical nerve root and the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V). Dr. Seletz notes that many patients involved in whiplash trauma will develop incapacitating severe headaches that may persist for months or even years following the injury. These headaches are often severe and begin in the suboccipital area and radiate to the vertex or to behind one eye; or they may be frontal or temporal.

Dr. Seletz believes that the 2nd cervical nerve root is most often involved in the generation of headaches, stating:

“The 2nd cervical nerve root is more vulnerable to trauma than other nerve roots because it is not protected by pedicles and facets.”

Dr. Seletz emphasizes that a major portion of the headaches associated with the whiplash syndrome are derived from a traction injury to the second cervical nerve root. The second cervical nerve root is particularly vulnerable to injury because it is not protected by pedicles and facets, as are the other cervical nerve roots. Also, the second cervical nerve root exits between the atlas and axis, “the point of greatest rotation of the head on the neck.”

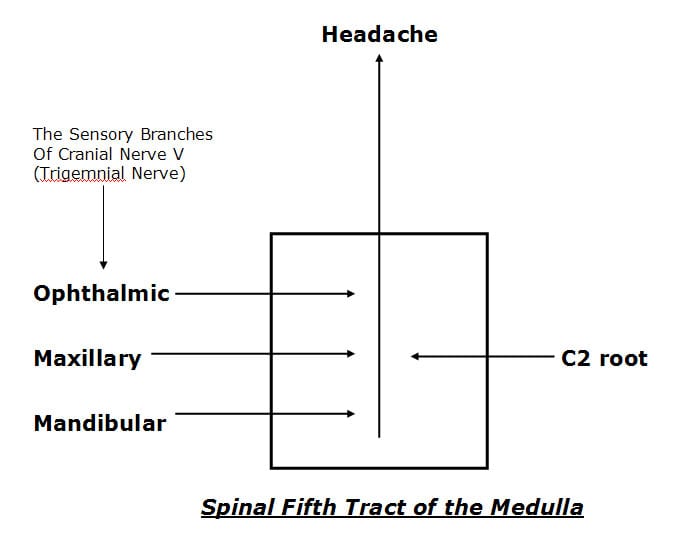

Dr. Seletz explains that sensory changes in any of the three sensory branches (ophthalmic, maxillary, mandibular) of the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V) are capable of producing headaches. He also explains that the three sensory branches of the trigeminal nerve communicate (synapse with) with the 2nd and 3rd cervical nerve roots in the upper neck in a nucleus he calls the spinal fifth tract of the medulla.

Dr. Seletz’s model of post-whiplash headache is quite simple:

1) Whiplash trauma injures the vulnerable 2nd cervical nerve root.

2) The sensory input change derived from the injured 2nd nerve root synapses in the spinal fifth tract of the medulla where it synaptically communicates with the branches of the trigeminal nerve.

3) The signal in the spinal fifth tract of the medulla is interpreted as a headache in one or more of the branches of the trigeminal nerve.

Dr. Seletz explains that the ophthalmic fibers of cranial nerve V descend the deepest into the cervical spine. Consequently, traumatized patients with an irritated 2nd nerve root often perceive their headache in the distribution of the ophthalmic branch, which is around and behind the eye.

Adding to the mechanism of chronic post-traumatic headache, Dr. Seletz notes that trauma causes hemorrhage, leading to the development of adhesions forming about the upper cervical nerve roots. He states that these nerve root adhesions are visible during surgical exposure. These nerve root adhesions chronically irritate the nerve roots, sending a signal into the spinal fifth tract of the medulla and ultimately causing chronic headache.

In summary, Dr. Seletz states:

“The physiological communication between the second cervical and the trigeminal nerves in the spinal fifth tract of the medulla [trigeminal-cervical nucleus] involves the first division of the trigeminal nerve [opthalamic] and thereby gives attacks of hemicrania with pain radiating behind the corresponding eye. This is the mechanism whereby a great many chronic and persistent headaches have their true origin in injury to the second cervical nerve.”

“Many headaches are not headaches at all, but really a pain in the neck.”

•••••

Although Drs. Jackson and Seletz described the neuroanatomical basis of headaches arising from the cervical spine in the 1940s and 1950s, “Cervicogenic Headache” was not officially recognized until 1983 by Sjaastad (6). In his 1983 article titled “Cervicogenic Headache” An Hypothesis, Sjaastad listed the diagnostic criteria for cervicogenic headache as:

- Precipitation of head pain by neck movement and/or sustained awkward head positioning.

- Precipitation of head pain by external pressure over the upper cervical or occipital region on the symptomatic side.

- Restriction of neck range of motion.

- Ipsilateral neck, shoulder, or arm pain of a rather vague nonradicular nature, or, occasionally, arm pain of a radicular nature.

- Unilaterality of the head pain, without sideshift.

- Head pain is moderate-severe, nonthrobbing, and nonlancinating, usually starting in the neck.

- Occasionally there is nausea, phonophobia, photophobia, dizziness, ipsilateral blurred vision, difficulties on swallowing, ipsilateral edema (mostly in the periocular area).

- The pain typically starts at the back of the head, spreading to frontal areas.

A recent (June 2011) PubMed search of the National Library of Medicine database using the key words “cervicogenic headache” listed 744 articles, with publication dates ranging from September 1942 to June 2011.

•••••

Perhaps the most detailed anatomical description for the physiological basis for cervicogenic headache was written by Australian physician and clinical anatomist Nikoli Bogduk, MD, PhD, in 1995. Dr. Bogduk published an article in the journal Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy titled (7):

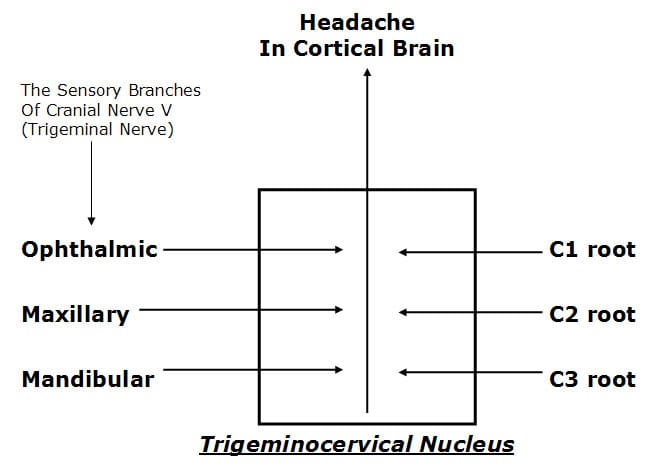

Anatomy and Physiology of Headache

In this article, Dr. Bogduk notes that all headaches have a common anatomy and physiology in that they are all mediated by the trigeminocervical nucleus, and are initiated by noxious stimulation of the endings of the nerves that synapse in this nucleus. “Trigeminocervical nucleus” is contemporary terminology for what Dr. Emil Seletz termed spinal fifth tract of the medulla. The trigeminocervical nucleus is a region of grey matter in the medulla of the brainstem that descends into the upper cervical spinal cord.

In agreement with Dr. Seletz above, Dr. Bogduk notes that the trigeminocervical nucleus receives afferents from all three branches (ophthalmic, maxillary, mandibular) of the trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V). In slight variance with Dr. Seletz, Dr. Bogduk’s detailed anatomical sections indicate that the trigeminocervical nucleus receives afferents from nerve roots C1, C2, and C3.

Consequently, irritation of any of the upper three cervical nerve roots can cause headaches. In addition, Dr. Bogduk stresses that irritation or injury to any tissue innervated by the upper cervical nerve roots can cause headaches.

Both Dr. Seletz and Dr. Bogduk indicate that the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve extends the farthest into the trigeminocervical nucleus, and consequently cervical afferent nerve irritation is most likely to refer pain to the frontal-orbital region of the head.

Both Dr. Seletz and Dr. Bogduk agree that the C1 and C2 nerve roots are particularly likely to be involved in the genesis of cervicogenic headache because the C1 and C2 spinal nerve roots “do not emerge through intervertebral foramina.” This make these nerve roots more vulnerable to stretch or compressive stresses.

Dr. Seletz commented that in his surgically managed cervicogenic headache patients he would find scar tissue or adhesions that were responsible for chronic C2 nerve root irritation. Dr. Bodguk’s anatomical sections further isolate these C2 nerve root post-traumatic adhesions at two locations:

- At the C2 dorsal root ganglion as it crosses the C1-C2 joint capsule.

- At the under belly of the inferior oblique muscle.

•••••

In 2005, Dr. David Biondi, an instructor in Neurology at Harvard Medical School, published an article titled (8):

Cervicogenic Headache:

A Review of Diagnostic and Treatment Strategies

Dr. Biondi notes that cervicogenic headache is a relatively common cause of chronic headaches with a prevalence as high as 20%. He notes that post-whiplash cervicogenic headache is particularly porne to chronicity.

Dr. Biondi notes that in the management of cervicogenic headache, drugs alone are often ineffective. He states, “Many patients with cervicogenic headache overuse or become dependent on analgesics.” He also notes that COX-2 inhibitors cause both gastrointestinal and renal toxicity after long-term use, and they cause an increased risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events.

Dr. Biondi is an osteopathic physician, and therefore has an understanding of manual and manipulative techniques. He states:

“All patients with cervicogenic headache could benefit from manual modes of therapy and physical conditioning.”

Dr. Biondi notes that the treatment of cervicogenic headache usually requires manipulation of the upper cervical facet joints, and that manipulative techniques are particularly well suited for the management of cervicogenic headache, including high velocity, low amplitude manipulation. These techniques are commonly used by chiropractors in the management of cervicogenic headaches.

In April of this year (2011), Dr. Maurice Vincent published a detailed review article pertaining to the relationship between the cervical spine and headache (9). In the article, Dr. Vincent lists five requirements for the diagnosis of cervicogenic headache. They are:

1) unilateral pain preponderance

2) reduction of cervical range of motion

3) pain in the ipsilateral shoulder or arm

4) attacks precipitation from triggering spots in the neck

5) precipitation from awkward neck positions.

These five requirements are all present in my patient Barbara:

Barbara was suffering from post-traumatic chronic cervicogenic headache. Recall that her “headache was triggered by sustained deep pressure at the inferior margin of the right inferior oblique muscle.” Consequently, my assessment included that Barbara was suffering from an ectopic depolarization of the C2 nerve root at the inferior margin of the right inferior oblique muscle; the electrical signal communicated with the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve in the trigeminocervical nucleus, creating a cortical brain perception of a headache around her right eye. As there is a history of trauma and 24 years of chronicity, it seems plausible that the primary nidus of C2 irritation was scar tissue or adhesions at the inferior oblique muscle, consistent with the writings of both Drs. Seletz and Bogduk. The irritation of the C2 nerve root is most likely aggravated by alignment and motion dysfunctions of the upper cervical spinal segments.

My clinical protocols included the following:

1) Analysis and chiropractic management of upper cervical spinal segmental alignment.

2) Analysis and chiropractic management of asymmetry of upper cervical spinal segmental movement.

3) Manual friction myotherapy at the inferior margin of the inferior oblique muscle. This is done in a effort to reduce the adverseness of adhesions and/or scar tissue that appeared to be irritating the C2 nerve root.

4) Low level laser therapy (in the office) and cryotherapy (homecare) to reduce inflammation subsequent to tissue work.

Barbara was so treated three times per week for four weeks, a total of twelve visits. The one-month re-evaluation showed a 100% resolution of both signs and symptoms. Twenty-four years chronicity and suffering resolved within one moth of manual therapy.

REFERENCES:

1) Jackson R, The Cervical Syndrome, Thomas, 1978.

2) Jackson R; The Cervical Syndrome As a Cause of Migraine. Journal of the American Medical Women’s Association. December 1947, Vol. 2, No. 12, pp. 529-534.

3) Seletz E; Craniocerebral Injuries and the Postconcussion Syndrome; Journal of the International College of Surgeons; January, 1957; 27(1):46-53.

4) Seletz E; Headache of Extracranial Origin; California Medicine; November 1958, Vol. 89, No. 5, pp. 314-17.

5) Seletz E; Whiplash Injuries, Neurophysiological Basis for Pain and Methods Used for Rehabilitation; Journal of the American Medical Association; November 29, 1958, pp. 1750 – 1755.

6) Sjaastad O; “Cervicogenic” Headache: An Hypothesis; Cephalagia; December 1983; 3(4):249-256.

7) Bogduk N; Anatomy and Physiology of Headache; Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy; 1995, Vol. 49, No. 10, pp. 435-445.

8) Biondi DM; Cervicogenic Headache: A Review of Diagnostic and Treatment Strategies; Journal of the American Osteopathic Association; April 2005, Vol. 105, No. 4 supplement, pp. 16-22.

9) Vincent MB; Headache and Neck; Current Pain Headache Report; April 5, 2011 [Epub].