Not everyone injured in a motor vehicle collision recovers completely. A percentage of those injured will suffer for years or sometimes even for decades. Documented examples of this chronic pain syndrome include:

- In 1964, the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (American) published a study where the author followed 145 whiplash-injured patients for more than two years. The author reported that after a minimum of two years, between 45% to 83% of the injured patients continued to suffer from pain.* (1)

*The author’s study initially included 266 injured patients, but at the follow-up assessment (more then 2 years later) only 145 were evaluated (121 of the original group were not evaluated at the two plus year follow-up). Of the 145 followed patients, 83% were still suffering pain symptoms. The author noted that if he assumed that 100% of the 121 subjects who were not evaluated were completely symptom free, then the incidence of chronic pain in the entire initial 266 patient set fell to 43%.

- In 1989, the journal Neuro-Orthopedics published a 12.5-year (mean duration) study on whiplash-injured patients. The authors reported that 62% continued to suffer from significant pain symptoms attributed to the motor vehicle collision 12.5 years later. (2)

- In 2000, the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology published a 7-year study on whiplash-injured patients. The authors reported that 39.6% continued to suffer from neck-shoulder pain 7 years after injury. This 39.6% chronic pain rate was three times greater than the pain noted in the matched control populations. (3)

- In 2005, the journal Injury published a 7.5 year prospective study on whiplash-injured patients. The authors reported that 21% of these patients continued to suffer from clinically relevant pain 7.5 years after injury. An additional 48% continued to suffer from nuisance pain at the 7.5-year analysis. (4)

- In 1990, the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (British) published a 10.8 year study on whiplash-injured patients. The authors reported that 40% of these patients continued to suffer from clinically significant pain 10.8 years after injury. An additional 40% continued to suffer from nuisance pain at the 10.8-year analysis. (5)

- In 1996, the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (British) published a 15.5-year study on whiplash-injured patients. The authors reported that 43% of these patients continued to suffer from clinically significant pain 15.5 years after injury. An additional 28% continued to suffer from nuisance pain at the 15.5-year analysis. (6)

- In 2002, the European Spine Journal published a 17-year study on whiplash-injured patients. The authors reported that 55% of these patients continued to suffer from residual pain 17 years after injury. Of those with residual symptoms, 25% suffered from neck pain every day, and 23% had pain radiating into their arm daily. (7)

- In 2006, the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (British) published a 30-year study on whiplash-injured patients. The authors reported that 15% of these patients continued to suffer from clinically significant pain 30 years after injury; their pain was such that they still required ongoing treatment. An additional 40% continued to suffer from nuisance pain at the 30-year analysis. (8)

•••••

In the vast majority of these chronic pain patients, secondary monetary gain does not appear to be the reason for their suffering. If secondary monetary gain were the motivation behind ongoing pain and suffering, such pain and suffering would resolve after receiving the monetary compensation. When an individual continues to complain of post-whiplash pain 2 plus, 7, 7.5, 10.8, 12.5, 15.5, 17, and even 30 years after the initial injury and after all possible monetary compensation has already been awarded, it is difficult to ascribe those chronic complaints to the desire to enhance monetary compensation. Several of the authors of the above studies made comments on this fact, including these:

“If the symptoms resulting from an extension-acceleration injury of the neck are purely the result of litigation neurosis, it is difficult to explain why 45% [minimum, could be as high as 83%] of the patients should still have symptoms two years or more after settlement of their court action.” (1)

“If symptoms were largely due to impending litigation it might be expected that symptoms would improve after settlement of the claim. Our results would seem to discount this theory, with the long-term outcome seeming to be determined before the settlement of compensation.” (2)

The fact that symptoms do not resolve even after a mean 10 years supports the conclusion that litigation does not prolong symptoms. (5)

Symptoms did not improve after settlement of litigation, which is consistent with previous published studies. (6)

“It is not likely that the patients exposed to motor vehicle accidents would over-report or simulate their neck complaint at follow-up 17 years after the accident, as all compensation claims will have been settled.” (7)

•••••

In 1997, a study published in the journal Pain reported that chronic pain whiplash-injured patients have an abnormal psychological profile (9). However, the authors noted that in their review, they were unable to find any evidence that appropriate psychotherapy was able to effectively treat the patient’s pain. Rather, the psychotherapy helped the patient deal with their pain, but it did not remove their pain. In contrast, the authors were able to effectively eliminate the patient’s abnormal psychological profile, essentially 100% of the time, if and only if they were able to establish an organic lesion causing the patient’s pain and effectively treating it. The authors reported that the abnormal psychological profile was the consequence of the chronic pain.

Other studies have also concluded that the whiplash-injured patient’s abnormal psychological profile is secondary to their chronic pain. As an example, in 1996, Squires and colleagues note (6):

Studies have found that patients that were psychologically normal at the time of injury will develop abnormal psychological assessments if their symptoms persisted for three months.

This study showed an “abnormal psychological profile in patients with symptoms after 15 years suggesting that this is both reactive to physical pain and persistent.”

In 2010, Rooker and colleagues note (8):

Whiplash-injured patients with a disability [including chronic pain symptoms] often develop an abnormal psychological profile.

Other studies have also concluded that chronic whiplash pain is not, as a rule, psychometric, but rather it has an organic basis. In 1997, a study published in the Journal of Orthopedic Medicine followed whiplash-injured patients and a matched control population for a period of 10 years (10). Neck pain was 8 times more prevalent in the whiplash group than in the control group. Paraesthesia was 16 times more prevalent in the whiplash group than in the control group. Headaches were 11 times more prevalent in the whiplash group than in the control group. The combination of both back pain and neck pain was 32 times more prevalent in the whiplash group than in the control group. Importantly, objectively, the x-rays showed that radiographic degenerative changes in the cervical spine appeared 10 years earlier in the whiplash group than in the control group. The authors reported:

“The prevalence of degenerative changes in the younger cervical spine [of the whiplash group] suggests that the condition has an organic basis.”

“Degenerative change and its association with neck stiffness support an organic basis for the symptoms that follow soft tissue injuries of the neck.”

•••••

In 2007, a study was published summarizing the basis of all pain, including chronic pain, in the journal Medical Hypothesis (11). The author, from the Division of Inflammation and Pain Research, Los Angeles Pain Clinic, cites studies to support these conclusions:

“The origin of all pain is inflammation and the inflammatory response.”

“Irrespective of the type of pain, whether it is acute or chronic pain, peripheral or central pain, nociceptive or neuropathic pain, the underlying origin is inflammation and the inflammatory response.”

“Activation of pain receptors, transmission and modulation of pain signals, neuroplasticity and central sensitization are all one continuum of inflammation and the inflammatory response.”

“Irrespective of the characteristic of the pain, whether it is sharp, dull, aching, burning, stabbing, numbing or tingling, all pain arises from inflammation and the inflammatory response.”

•••••

In 1975, Stonebrink (12) addresses that the last phase of the pathophysiological response to trauma is tissue fibrosis. Boyd in 1953 (13), Cyriax in 1983 (14), and Majno/Joris in 2004 (15) note that there is tissue fibrosis subsequent to trauma. This fibrosis of repair subsequent to soft tissue trauma creates problems that can adversely affect the tissues and the patient for years, decades, or even forever.

As an example, Cyriax (14):

“Fibrous tissue is capable of maintaining an inflammation, originally traumatic, as a result of a habit continuing long after the initial [cause] has ceased to operate.”

Connecting the dots, I propose the following model:

Tissue trauma, including whiplash trauma,

heals with varying degrees of fibrous tissue.

↓

Post-traumatic fibrous tissue is capable of maintaining an inflammatory response long after the initial cause has ceased to exist.

↓

This inflammatory fibrous tissue alters the threshold of the pain neurons, increasing the probability of chronic pain perception.

•••••

In 1971, biochemists Sune K. Bergström (Sweden; d.2004), Bengt I. Samuelsson (Sweden) and John R. Vane (United Kingdom; d. 2004) determined that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) could inhibit the synthesis of prostaglandins from the toxic fat arachidonic acid. They subsequently jointly received the 1982 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their research on prostaglandins. The official Nobel Prize press release acknowledged:

“Prostaglandins are continuously formed in the stomach, where they prevent the tissue from being damaged by the hydrochloric acid. If the formation of prostaglandins is blocked a peptic ulcer can rapidly be formed.”

As a consequence of the 1982 Nobel Prize in Medicine or Physiology, scientists and healthcare providers have a much better understanding of the mechanisms of how aspirin and other nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs reduce pain, but also increase the risk for gastrointestinal bleeding and kidney damage. In an effort to reduce the gastrointestinal bleeding, a new class of NSAIDs, the COX-2 inhibitors, was developed. These drugs are also known as cyclo-oxygenase 2 inhibitors or ‘coxibs’, and the major brand names are Vioxx and Celebrex.

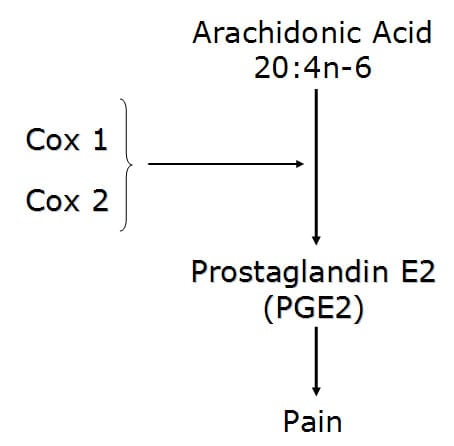

Cox enzymes convert the omega-6 fatty acid arachidonic acid into the pro-inflammatory pain producer prostaglandin E2 (PGE2).

In 2002, a study published in the European Spine Journal reported that of the 55% of whiplash-injured patients with pain 17 years after their injury, 53% of the patients were still using analgesics to manage their pain (7). Of these:

- 29% used analgesics 2-6 times per week

- 46% used analgesics 7-30 times per week

- 17% used analgesics more than 30 times per week

Although non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs inhibit the genesis of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and subsequently reduce pain, there are problems with habitual consumption of these products in the management of chronic pain syndromes, including the chronic pain that is often observed following whiplash injury (7). Importantly, habitual consumption of NSAIDs for chronic pain conditions has been associated with a number of deleterious health events, including:

- End stage renal disease (16)

- Gastrointestinal Bleeding (17, 18)

- Myocardial infarction (18, 19, 20)

- Stroke (18, 20)

- Alzheimer’s and other dementias (21)

- Hearing loss (22)

- Erectile dysfunction (23)

In 2003, the journal Spine published a study stating (24):

“Adverse reactions to nonsteroidal antiinflammatory (NSAID) medication have been well documented.”

“Gastrointestinal toxicity induced by NSAIDs is one of the most common serious adverse drug events in the industrialized world.”

“The newer COX-2-selective NSAIDs are less than perfect, so it is imperative that contraindications be respected.”

There is “insufficient evidence for the use of NSAIDs to manage chronic low back pain, although they may be somewhat effective for short-term symptomatic relief.”

In 2006, a study published in Surgical Neurology stated (25):

“The use of NSAID medications is a well-established effective therapy for both acute and chronic nonspecific neck and back pain.”

“Extreme complications, including gastric ulcers, bleeding, myocardial infarction, and even deaths, are associated with their [NSAIDs] use.”

Blockage of the COX enzyme [with NSAIDs] inhibits the conversion of arachidonic acid to the very pro-inflammatory prostaglandins that mediate the classic inflammatory response of pain (dolor), edema (tumor), elevated temperature (calor), and erythema (rubor).

“More than 70 million NSAID prescriptions are written each year, and 30 billion over-the-counter NSAID tablets are sold annually.”

“5% to 10% of the adult US population and approximately 14% of the elderly routinely use NSAIDs for pain control.”

Almost all patients who take the long-term NSAIDs will have gastric hemorrhage, 50% will have dyspepsia, 8% to 20% will have gastric ulceration, 3% of patients develop serious gastrointestinal side effects, which results in more than 100,000 hospitalizations, an estimated 16,500 deaths, and an annual cost to treat the complications that exceeds 1.5 billion dollars.

“NSAIDs are the most common cause of drug-related morbidity and mortality reported to the FDA and other regulatory agencies around the world.”

One author referred to the “chronic systemic use of NSAIDs to ‘carpet-bombing,’ with attendant collateral end-stage damage to human organs.”

COX 2 inhibitors [Celebrex], designed to alleviate the gastric side effects of COX 1 NSAIDs, are “not only associated with an increased incidence of myocardial infarction and stroke but also have no significant improvement in the prevention of gastric ulcers.”

•••••

There are effective nontoxic alternatives to NSAIDs in the management of chronic spinal pain. A well-respected physician who is an advocate of these alternative approaches to chronic pain management is Joseph Charles Maroon, MD. Dr. Maroon is a neurosurgeon from the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. Dr. Maroon specializes in painful degenerative spinal diseases, and he is also the neurosurgeon for Pro Football’s Pittsburgh Steelers.

Recently (2006 and 2010), Dr. Maroon has published two studies and one book on the efficacy of natural anti-inflammatory agents for pain relief (25, 26, 27). The effective products Dr. Maroon details include:

Omega-3 Essential Fatty Acids (fish oil)

White willow bark

Curcumin (turmeric)

Green tea

Pycnogenol (maritime pine bark)

Boswellia serrata resin (Frankincense)

Resveratrol

Uncaria tomentosa (cat’s claw)

Capsaicin (chili pepper)

In his writings, Dr. Maroon discusses the biological plausibility for the use of each of these products, as well as their therapeutic doses. He particularly emphasizes the viability of omega-3 essential fatty acids, noting that these oils powerfully inhibit the production of both pro-inflammatory prostaglandins and pro-inflammatory leukotrienes. In his 2006 study (25), Dr. Maroon found that he could eliminate pain medication in 59% of his study subjects.

Other studies also support the utilization of omega-3 fatty acids (fish oil) in an effort to achieve an anti-inflammatory state:

In 2006, the journal Arthritis Research & Therapy published a study noting that an anti-inflammatory dose of fish oil had to be a minimum of 2,700 g/d of EPA plus DHA (the active anti-inflammatory ingredients in fish oil) (28).

In 2007, the journal Pain published a study also study noting that an anti-inflammatory dose of fish oil had to be a minimum of 2,700 mg/d of EPA plus DHA (29).

Both studies (28, 29) indicated that it might take a period of 2-3 months before maximum benefit of fish oil supplementation to be observed.

In 2010, The Clinical Journal of Pain presented a case series of patients suffering from chronic neuropathic pain, including patients injured in whiplash collisions (30). The authors noted that in these more difficult neuropathic pain patients, that more aggressive fish oil supplementation may be required to achieve a good clinical outcome. They suggest doses of EPA plus DHA between 2400-7500 mg/d. Their case series was very successful with these high doses of fish oil, stating:

“These patients had clinically significant pain reduction, improved function as documented with both subjective and objective outcome measures up to as much as 19 months after treatment initiation.”

“No serious adverse effects were reported.”

“This first-ever reported case series suggests that omega-3 fatty acids may be of benefit in the management of patients with neuropathic pain.”

•••••

In summary, it is inevitable that some patients injured in motor vehicle collisions will develop chronic pain syndrome. The cause of their chronic pain is rarely psychometric. Rather their pain usually has an organic basis, which includes post-traumatic scarring with persistent inflammation. Inflammation predisposes tissues to pain generation and perception. Management with anti-inflammatory agents makes sense. However, NSAIDs taken for chronic pain syndromes are associated with a number of serious adverse events, including death. There is good evidence that there are a number of alternative natural products for pain management that are both safe and effective, especially omega-3 fish oils. Alternative health care practioners routinely uses these products in the management of chronic pain patients, including those injured in whiplash trauma. The results are improved outcomes, few if any side effects, and great patient satisfaction.

•••••

References:

1) Macnab, I; Acceleration Injuries of the Cervical Spine; Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (American); Vol. 46, No. 8, December 1964.

2) Hodgson SP, Grundy M; Whiplash Injuries: Their Long-term Prognosis and its Relationship to Compensation; Neuro-Orthopedics; No.7, 1989, pp. 88-91.

3) Berglund A, Alfredsson L, Cassidy JD, Jensen I, Nygren A; The association between exposure to a rear-end collision and future neck or shoulder pain; Journal of Clinical Epidemiology; 2000; 53:1089-1094.

4) Tomlinson PJ, Gargan MF, Bannister GC. The fluctuation in recovery following whiplash injury: 7.5-year prospective review. Injury. Volume 36, Issue 6, June 2005, Pages 758-761.

5) Gargan MF, Bannister GC. Long-Term Prognosis of Soft-Tissue Injuries of the Neck. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (British); Vol. 72-B, No. 5, September 1990, pp. 901-3.

6) Squires B, Gargan MF, Bannister CG. Soft-tissue Injuries of the Cervical Spine: 15-year Follow-up. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (British). November 1996, Vol. 78-B, No. 6, pp. 955-7.

7) Bunketorp L, Nordholm L Carlsson J; A descriptive analysis of disorders in patients 17 years following motor vehicle accidents; European Spine Journal, 11:227-234, June 2002.

8) Rooker J, Bannister M, Amirfeyz R, B. Squires, M. Gargan, G. Bannister; Whiplash Injury 30-Year follow-up of a single series; Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery – British Volume; 2010; Volume 92-B, Issue 6, pp. 853-855.

9) Wallis B, Lord S, Bogduk N; Resolution of Psychological Distress of Whiplash Patients Following Treatment by Radiofrequency Neurotomy: A randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial; Pain, October 1997; Vol. 73, No. 1; pp. 15-22.

10) Gargan MF, Bannister GC. The Comparative Effects of Whiplash Injuries. The Journal of Orthopaedic Medicine, 19(1), 1997, pp. 15-17.

11) Omoigui S; The biochemical origin of pain: The origin of all pain is inflammation and the inflammatory response: Inflammatory profile of pain syndromes; Medical Hypothesis; 2007, Vol. 69, pp. 1169 – 1178.

12) Stonebrink, R.D., D.C., “Physiotherapy Guidelines for the Chiropractic Profession,” ACA Journal of Chiropractic, (June1975), Vol. IX, p.65-75.

13) Boyd, William, M.D., Pathology, Lea & Febiger, (1953).

14) Cyriax J, Orthopaedic Medicine, Diagnosis of Soft Tissue Lesions, Bailliere Tindall, Vol. 1, (1982).

15) Majno, Guido and Joris, Isabelle, Cells, Tissues, and Disease: Principles of General Pathology, Oxford University Press, 2004.

16) Perneger PV, Whelton PK, Klag MJ; Risk of Kidney Failure Associated with the Use of Acetaminophen, Aspirin, and Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs; New Eng J Med, Number 25, Volume 331:1675-1679, December 22, 1994.

17) Wolfe MM, Lichtenstein DR, Singh, G; Gastrointestinal Toxicity of Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs; The New England Journal of Medicine June 17, 1999.

18) Vaithianathan R, Hockey PM, Moore TJ, Bates DW; Iatrogenic Effects of COX-2 Inhibitors in the US Population; Drug Safety 2009; 32 (4): 335-343.

19) Helin-Salmivaara A, Virtanen A, Vesalainen R, Gronroos JM, Klaukka T, Idanpaan-Heikkila JE, Huupponen R; NSAID use and the risk of hospitalization for first myocardial infarction in the general population: a nationwide case-control study from Finland; European Heart Journal May 26, 2006.

20) Trelle S, Reichenbach S, Wandel S, Hildebrand P, Tschannen B, Villiger PM, Egger M; Cardiovascular safety of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: Network meta-analysis; British Medical Journal; January 11, 2011; Vol. 342:c7086.

21) Breitner JC, Haneuse SJPA, Walker R, Dublin S, Crane PK, Gray SL, Larson EB, Risk of dementia and AD with prior exposure to NSAIDs in an elderly community-based cohort; Neurology; June 2, 2009; Vol. 72, No. 22; pp. 1899-905.

22) Curhan SG, Eavey R, Shargorodsky J, Curhan GC; Analgesic Use and the Risk of Hearing Loss in Men; The American Journal of Medicine; March 2010; Vol. 123; No. 3; pp. 231-237.

23) Gleason JM, Slezak JM, Jung H, Reynolds K, Van Den Eeden SK, Haque R, Quinn VP, Loo RK, Jacobsen SJ; Regular nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and erectile dysfunction; Journal of Urology; April 11, 2011; Vol. 185; No. 4; pp. 1388-93.

24) Giles LGF, Muller R; Chronic Spinal Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial Comparing Medication, Acupuncture, and Spinal Manipulation; Spine; July 15, 2003; 28(14):1490-1502.

25) Maroon JC, Bost JW; Omega-3 Fatty acids (fish oil) as an anti-inflammatory: an alternative to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for discogenic pain; Surgical Neurology; 65 (April 2006) 326– 331.

26) Maroon JC, Bost JW, Maroon A; Natural anti-inflammatory agents for pain relief; Surgical Neurological International; December 2010.

27) Maroon JC; Fish Oil, The Natural Anti-Inflammatory, Basic Health, 2006.

28) Cleland CG, James MJ, Proudman SM; Fish oil: what the prescriber needs to know; Arthritis Research & Therapy; Volume 8, Issue 1, 2006, p. 402.

29) Goldberg RJ Katz J; A meta-analysis of the analgesic effects of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation for inflammatory joint pain; Pain; May 2007, 129(1-2), pp. 210-223.

30) Ko GD, Nowacki NB, Arseneau L, Eitel M, Hum A; Omega-3 Fatty Acids for Neuropathic Pain: Case Series; The Clinical Journal of Pain; February 2010, Vol. 26, No, 2, pp 168-172.