The primary region of the human body to be injured in a whiplash accident is the neck. The whiplash injury is an inertial injury to the neck. This means that there is no direct impact, blow, or contact to the neck. Rather, the injury is indirect, and there is no contact. Another well-known example of a neck inertial injury is “shaken baby syndrome.” The injury to the baby’s neck is indirect, or inertial.

During the whiplash mechanism, two large pieces of inertial mass, the head and the trunk, tend to move in opposite directions. As an example, in a rear end collision, the trunk moves forward with the struck vehicle, while the inertial mass of the head leaves the head behind. The neck, existing between these two large inertial masses, is subjected to mechanical stresses, and may become injured. The injury occurs because there are mechanical stresses to the structures of the neck that occur as a consequence of inertial loading.

The cranial-cervical junction and the upper cervical spine are a mechanically unique region of the spinal column. Their mechanically unique characteristics increase the vulnerability of the upper cervical spine tissues to inertial injury. Four relevant unique mechanical characteristics to this discussion include:

1) The center of mass of the head exists at the location of the sella turcica, the bony location of the pituitary gland. A mechanical lever arm exists between the sella turcica and the joints of the upper cervical spine, especially the occiput, first cervical vertebrae (C1, or atlas), and the second cervical vertebrae (C2 or axis).

When the head becomes inertially involved in the mechanism of a trauma, this unique lever arm increases the inertial injury to the cranial-upper cervical spine region.

2) A general biomechanical principle includes the understanding that there is a trade-off between mobility and stability. Joints that have greater mobility have reduced stability. Joints that have great stability have reduced mobility. Joints that have great mobility have increased vulnerability to injury (including inertial injury).

Although it is not commonly understood, 55% of cervical spine (neck) rotation (turning to the left or right) occurs at a single joint. This joint possesses great mobility, but at a price of reduced stability and increased vulnerability to inertial injury. The joint is the atlas-axis joint (C1-C2).

3) Very little motion occurs between the skull (occiput bone, CO) and the atlas vertebrae (C1). Consequently, during inertial loading, the occiput bone and the atlas vertebrae often function together. This increases the mechanical stresses between the atlas (C1) and the axis (C2). Once again, the atlas-axis joint (C1-C2) has increased vulnerability to inertial injury.

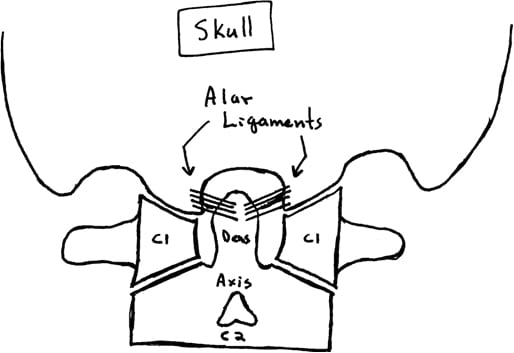

4) A main stabilizing ligament of the cranial-cervical region is called the alar ligament. The alar ligaments exist between the odontoid process of the axis (C2) and the lateral masses of the occiput bone.

The alar ligaments connect the odontoid process (dens) of the axis vertebrae (C2) to the occipital condyles of the occiput bone of the skull.

•••••

There is no doubt that a percentage of whiplash injured patients will develop chronic pain that does not improve or go away after all possible monetary compensation has been obtained. Representative examples include:

• A 1990 study reviewed the long-term status of whiplash-injured patients. They reviewed 43 patients who had sustained soft-tissue injuries of the neck after a mean 10.8 years. Of these, only 12% had recovered completely and 88% suffered from residual symptoms. Of these residual symptoms, 28% were intrusive and 12% were severe. After two years, symptoms did not alter with further passage of time, remaining chronic. This indicates that 40% of whiplash-injured patients continued to suffer from significant residual symptoms more than a decade after being injured.

(Gargan, Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (British), 1990)

• A 1996 study reviewed the long-term status of whiplash-injured patients 15.5 years after injury. The authors documented that 70% of the patients continued to complain of symptoms referable to the original accident. In addition, 33% complained of intrusive symptoms and 10% were unable to work and relied heavily on analgesics or alternative therapy. This means that 43% had significant problems caused by whiplash injury more than 15 years after being injured. Surprisingly, these authors also documented that 60% of symptomatic patients had not seen a doctor in the previous five years because the doctors were unable to help them, and that 18% of these patients had taken early retirement due to their health problems, which they related to the whiplash injury. They also documented that whiplash symptoms do not improve after settlement of litigation.

• A 2002 study looked at the health status of whiplash-injured patients 17 years after injury. At the time, this was the longest follow-up study on whiplash-injured patients published. The authors documented that 55% of the patients still suffered from pain caused by the original trauma 17 years later.

(Bunketorp, European Spine Journal, 2002)

• A 2007 review article documents that between 15-40% of those who are injured in a motor vehicle collision will suffer from ongoing chronic pain.

(Schofferman, Journal of the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, 2007)

• A 2005, 7.5-year prospective study on whiplash-injured patients found that 21% had intrusive symptoms that interfered with work and leisure, and required continued treatment and drugs. In addition, 2% of these whiplash-injured patients had severe pain and problems that required ongoing medical investigations and drugs. This means that 23% of whiplash-injured patients had significant problems more than 7 years after being injured.

(Tomlinson, Injury, 2005)

• A 2009 review article pertaining to whiplash injury and including 100 citations, thoroughly reviewed 15 studies pertaining to whiplash-injury outcomes. The authors document that fewer than 50% of all patients made a full recovery and that 4.5% are permanently disabled. In addition, they document that whiplash-injured patients are 5 times more likely to suffer from chronic neck pain than control populations. The view that a whiplash-injured patient’s symptoms will improve once litigation has finished “is unsupported by the literature.”

(Bannister, Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, British, 2009)

• A very recent study (June 2010), published the assessment of whiplash-injured patients 30 years after injury, making this the longest follow-up of whiplash-injured patients to date. Once again, this study shows that a significant number of those injured in whiplash trauma will suffer with chronic symptoms. Thirty years after being injured, 40% of patients retain nuisance symptoms and 15% have significant symptoms and impairments, requiring ongoing treatment.

(Rooker, Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, British, 2010)

Again, with there being no doubt to the chronicity of symptoms for some patients following whiplash trauma, numerous clinical investigations have been performed in the assessment of the tissue origin of these symptoms. These investigations have included the careful fluoroscopic insertions of anesthetic needles using gold-standard protocols and techniques. The majority of these studies have focused on the tissues of the lower cervical spine. Since 1993, it has been firmly established the primary tissue source for chronic whiplash injury symptoms are the facet joints of the lower cervical spine, with the annulus of the disc being a close second source.

(Bogduk, Pain, 1993)

However, recently, researchers have turned their attention to the tissues of the upper cervical spine as a source of chronic symptoms following whiplash trauma, especially if the symptom complex includes headaches. Specifically, these researchers have focused on the alar ligaments. As noted above, the alar ligaments are particularly vulnerable to inertial loading injury.

Historically, the most important whiplash injury physician was Ruth Jackson, MD. Ruth Jackson was born in 1902 and graduated from Baylor University College of Medicine in Dallas in 1928. In 1937, she became the first woman to be certified by the American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery. From 1936 to 1941, Dr. Jackson was Chief of Orthopedics at Parkland Hospital in Fairmont, Texas. In 1945, she had her own private clinic built in Dallas, retiring in 1989 at the age of 87.

In her career, Dr. Jackson published more than twenty-five articles, and she lectured extensively in the United States and throughout the world. Dr. Jackson had a special interest in injuries of the cervical spine. Her interest arose after a neck injury she sustained in a motor-vehicle accident. In 1956 she published her acclaimed, authoritative book entitled The Cervical Syndrome. The fourth and final edition of her book was published in 1978. Dr. Jackson personally treated more than 20,000 whiplash-injured patients.

(Jackson, The Cervical Syndrome, 1978)

In her 1978 book, Dr. Jackson discusses the mechanics of the alar ligament injury from whiplash trauma. She also discussed documentation of these injuries using stress radiographs of the upper cervical spine.

After Computed Tomography (CT) scanning became more available, the documentation of alar ligament injury from whiplash trauma became more precise and definitive than the stress radiography methods of Dr. Ruth Jackson. The CT scanning procedure recommended consists of using high-resolution images of the ligaments of the occiput-atlas-axis complex while the patient is in a position of maximum upper cervical spine and head rotation.

(Panjabi, Journal of Spinal Disorders, 1991)

(Panjabi, Journal of Orthopedic Research, 1991)

(Dvorak, Spine, 1987)

Recent advances in MR imaging have further enhanced the assessment of the health of the alar ligaments, and have eliminated the concerns of excessive exposure to ionizing radiation coupled with CT technology. These studies have specifically compared the status of alar ligament health in chronic whiplash patients and compared them to asymptomatic control populations. A pioneering such study appeared in the journal Neurology in 2002, and was titled:

MRI assessment of the alar ligaments in the late stage of whiplash injury:

A study of structural abnormalities and observer agreement

These authors were able to characterize and classify structural changes in the alar ligaments in the late stage of whiplash injuries by using proton density weighted MRI technology, and evaluate the reliability and the validity of their procedures. They studied 92 whiplash-injured and 30 uninjured individuals who underwent proton density-weighted MRI of the cranial-cervical junction in three orthogonal planes. They concluded:

“Whiplash trauma can cause permanent damage to the alar ligaments, which can be shown by high-resolution proton density-weighted MRI.”

The authors of this study made the following important points:

• Alar ligaments consist primarily of collagen proteins with a few elastic fibers. In contrast to elastic fibers, which can tolerate elongation up to 200% before failure, collagen ligaments will fail at only 8% elongation. Consequently, the alar ligaments are particularly vulnerable to traumatic stretching loads.

• The cranial-cervical ligaments are very vulnerable to sudden acceleration and/or deceleration of the head.

• Several studies have documented traumatic alar ligament ruptures or injuries from whiplash trauma mechanisms.

• Plain cervical radiographs are usually normal following whiplash injury.

• The strength of the MRI magnet is important. They suggest that the strength be at least 1.5 tesla.

• The thickness of the section slices is important. They suggest that the slices not be less than 2 mm thick from the foramen magnum to the base of the dens. A slice thickness of 2 mm gives excellent spatial resolution of injured alar ligaments.

• T2-weighted images give inadequate discrimination between ligament, bone and soft tissue due to a low signal-to-noise ratio.

• T1-weighted images give poor contrast resolution and thus less ability to differentiate small variations in signal and therefore to assess injury.

• “A proton-density weighted sequence is the technique of choice for assessment of [alar] ligamentous abnormalities.”

• This study confirms that the alar ligaments are vulnerable to whiplash trauma, “and that the severity of the lesions can be graded using high-resolution MRI.”

• Whiplash trauma can cause permanent damage to the alar ligaments, and this damage can be shown by high-resolution proton density-weighted MRI.

• Alar ligament damage can take up to 2 years for complete healing.

• Cranial cervical junction ligament injury may prove to be the structural substrate for the chronic whiplash syndrome.

•••••

In 2005, a follow-up study was published in the Journal of Neurotrauma, titled:

Whiplash-Associated Disorders Impairment Rating:

Neck Disability Index Score According to Severity of MRI Findings of Ligaments and Membranes in the Upper Cervical Spine

These authors evaluated the ligaments of the upper cervical spine with proton-density weighted MR imaging, comparing it to pain and functional disability in whiplash-injured patients. The authors found:

“Symptoms and complaints among [whiplash-injured] patients can be linked with structural abnormalities in ligaments and membranes in the upper cervical spine, in particular the alar ligaments.”

The authors of this study made the following important points:

• Whiplash can injure the ligaments of the upper cervical spine.

• Injury to the ligaments of the upper cervical spine can be imaged with proton-density weighted MRI.

• “Post-traumatic changes of the alar ligaments have been proposed to be the cause of chronic pain in patients after whiplash.”

• The alar and transverse ligaments, and membranes in the upper cervical spine, as well as the lesions of these structures, can be visualized by high resolution MRI. “Thus, it now seems possible to demonstrate physical evidence of a neck injury in WAD patients.”

• Documented lesions to the alar ligaments were associated with more severe chronic whiplash symptoms.

• Chronic whiplash subjective symptoms and complaints can be a consequence of injuries to ligaments and membranes in the cranial-cervical junction.

• “The alar ligaments appeared to be the most important structure in a whiplash trauma, as it was the structure with the most frequent high-grade MRI abnormalities.”

• Alar ligament abnormalities also show the most consistency with disability scores.

• “Lesions of the alar ligaments can be a common denominator in explaining the pain and functional disability in the neck after a WAD trauma.”

• Women appeared to be more injured, explained by the “fact that the neck muscles are weaker in females, thus making their neck structures more vulnerable when under the influence of abrupt external forces.”

• “In summary, the present study shows that increasing severity of MRI findings of soft tissue structures in the upper cervical spine is related to increasing levels of neck pain and functional disability, as experienced by persons with a diagnosis of [whiplash injury].”

•••••

Later in 2005, the Journal of Neurotrauma published another study titled:

Head Position and Impact Direction in Whiplash Injuries:

Associations with MRI-Verified Lesions of Ligaments and

Membranes in the Upper Cervical Spine

These authors compared magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings of soft tissue structures in the upper cervical spine of whiplash-injured patients, a control population, and specific facts regarding the mechanism of injury. They were able to determine that the alar ligaments of the upper cervical spine were most vulnerable to injury when the patient’s “head/neck was turned to one side at the moment of collision.” The authors also made the following important points:

• Since the late 1980s it has been known that the alar ligaments could be injured from neck trauma, especially if the head is rotated at time of accident.

• The alar ligaments could be irreversibly overstretched or ruptured when the head is rotated and bent by the impact of whiplash trauma.

• There is growing evidence that whiplash injury is linked to soft tissue lesions in the cranial-cervical junction.

• The patients who had their head rotated at the instant of collision had more often injuries of the alar ligaments than those with their head in a neutral position.

• In rear end collisions, the alar ligament most likely to be injured was on the side opposite of head rotation. [If the head was turned to the left, the usual alar ligament injury was on the right].

• The alar ligaments are the most injured from neck trauma, especially if the head is rotated at time of accident.

• Alar ligaments can be irreversibly overstretched or ruptured when the head is rotated and bent by impact trauma.

• An abnormal alar ligament is the strongest predictor for severity of subjective symptoms and functional disability in whiplash-injured patients.

• The severity of injury to the alar and transverse ligaments depends on head rotation at the moment of collision.

• The best diagnostic tool to assess injury to the upper cervical ligaments and membranes is the proton density-weighted MRI examination.

• The alar ligaments are particularly vulnerable when the head is rotated and bent by impact trauma, “especially in unexpected rear-end collision.”

• Head rotation and awareness are more important than speed, type of headrest, sitting position, and fitness level when considering injury from whiplash trauma.

• Upper cervical ligament injuries represent “chronic lesions” that are responsible for chronic WAD pain.

•••••

In 2006, the journal Spine published an article titled:

Magnetic Resonance Imaging Assessment of Craniovertebral Ligaments and Membranes After Whiplash Trauma

These authors presented a review the literature on soft tissue lesions of the upper cervical spine in whiplash trauma with focus on neuroimaging. They concluded:

“Whiplash trauma can damage soft tissue structures of the upper cervical spine, particularly the alar ligaments”

The authors of this study also made the following important points:

• “Most investigators who have studied the natural history of whiplash patients have found long-term symptoms in 24% to 70%, among whom 12% to 16% are severely impaired many years after the accident interfering with their job and everyday activities.”

• Whiplash trauma can damage soft tissue structures of the upper cervical spine, particularly the alar ligaments.

• The soft tissues of the cranial-cervical joints can be imaged by use of high-resolution proton-density weighted MR imaging.

• “The alar ligaments are particularly vulnerable to neck trauma when the head is rotated at the moment of impact.”

“When the head rotates, the alar ligaments twist around the dens. Reaching 90° rotation, these ligaments are maximally tightened and obtain an anteroposterior orientation. Not unexpected, such tightened anteroposteriorly oriented alar ligaments are more vulnerable to hyperextension-hyperflexion trauma than relaxed, transversely oriented ligaments.”

• “Our findings add support to the hypothesis that injured soft tissue structures in the upper cervical spine, particularly the alar ligaments, play an important role in the understanding of the chronic whiplash syndrome.”

• To best examine the alar ligaments with MRI, proton-density weighted formatting should be used (not T1- and T2-weighted sequences), the magnet should have a least 1.5 Tesla strength, and the slice thickness should not exceed 2 mm.

• “Injured soft tissue structures in the upper cervical spine, particularly the alar ligaments, play an important role in the understanding of the chronic whiplash syndrome.”

•••••

In 2009, the journal Pain Research and Management published an article titled:

Dynamic kinemagnetic resonance imaging in whiplash patients

These authors presented a study comparing the motion of the upper cervical spine in chronic whiplash-injured patients with that of normal controls, and comparing both groups with findings from proton-density weighted MR imaging. They concluded:

Whiplash patients with longstanding symptoms had both more abnormal signals from the alar ligaments and more abnormal movements on dMRI at the Occiput-C2 level than controls.

The authors of this study also made the following important points:

• On average, 30% (range 11% to 42%) of people with acute whiplash develop chronic whiplash symptoms.

• “Injury to the alar ligaments associated with neck sprain could be a cause of pain and disability among these [chronic whiplash] patients.”

• Whiplash injury to the upper cervical spine can cause balance disturbance, dizziness, visual problems and jaw problems.

• The stability of the cranial-cervical junction is primarily provided by the alar and transverse ligaments.

• “The alar ligaments restrain rotation of the upper cervical spine.”

• “The alar ligaments may be irreversibly overstretched or even ruptured in unexpected rear-end collisions.”

• Alar ligament integrity can be assessed using high-resolution proton density-weighted dynamic MRI.

• Chronic whiplash patient symptoms attributable to Occiput-C1-C2, include:

Neck pain

Headache

Upper limb symptoms

Lower limb symptoms

Loss of balance

Some tongue numbness

• “Because of the lack of a disc and the horizontal nature of the facet joints, the stability of the atlanto-axial complex depends mainly on the ligaments and muscles.”

• 55% of the rotation of the cervical spine occurs at the C1-C2 joint.

5% of the rotation of the cervical spine occurs at the Occiput-C1 joint.

40% of the rotation of the cervical spine occurs at C2-C7.

• “Symptoms and complaints among WAD patients can be linked with structural abnormalities of the ligaments and membranes of the upper cervical spine, particularly the alar ligaments.”

•••••

ENDING REMARKS:

The discussion presented here indicates the following pertaining to the alar ligaments of the upper cervical spine:

1) They can sustain inertial injuries during whiplash trauma.

2) The injuries to the alar ligaments can be responsible for chronic whiplash symptoms.

3) Alar ligament injury can cause neck pain, but also headache, tinnitus, vertigo, light-headedness, unsteadiness, etc.

4) Alar ligament injuries are often permanent.

5) Alar ligament injuries are best diagnosed using proton density MR imaging.

Alar ligament problems pose both mechanical and proprioceptive problems for the patient. Experience indicates that carefully applied chiropractic adjustments to this sensitive spinal region can significantly improve and help manage these otherwise very difficult chronic injuries.

REFERENCES

Gargan MF, Bannister GC. Long-Term Prognosis of Soft-Tissue Injuries of the Neck. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (British); Vol. 72-B, No. 5, September 1990, pp. 901-3.

Squires B, Gargan MF, Bannister CG. Soft-tissue Injuries of the Cervical Spine: 15-year Follow-up. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (British). November 1996, Vol. 78-B, No. 6, pp. 955-7.

Schofferman J, Bogduk N, Slosar P.; Chronic whiplash and whiplash-associated disorders: An evidence-based approach; Journal of the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons; October 2007;15(10):596-606.

Bunketorp L, Nordholm L, Carlsson J; A descriptive analysis of disorders in patients 17 years following motor vehicle accidents; European Spine Journal, June 2002; 11:227-234.

Tomlinson PJ, Gargan MF, Bannister GC. The fluctuation in recovery following whiplash injury: 7.5-year prospective review. Injury. Volume 36, Issue 6, June 2005, Pages 758-761.

Bannister GC, Amirfeyz R, Kelley S, Gargan MF. Whiplash Injury. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (British). July 2009, Vol. 91B, no. 7, pp. 845-850.

Rooker J, Bannister M, Amirfeyz R, Squires B, Gargan M, Bannister G; Whiplash Injury: 30-Year follow-up of a single series; Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery – British Volume, Volume 92-B, Issue 6, pp. 853-855.

Bogduk N, Aprill C; On the nature of neck pain, discography and cervical zygapophysial joint blocks; Pain. August 1993;54(2):213-7.

Jackson R, The Cervical Syndrome, Thomas, 1978.

Panjabi M, Dvorak J, Crisco J, Oda T, Hilibrand A, Grob D; Journal of Spinal Disorders; June 1991;4(2):157-67.

Panjabi M, Dvorak J, Crisco JJ, Oda T, Wang P, Grob D; Effects of alar ligament transection on upper cervical spine rotation. Journal of Orthopedic Research. July 1991;9(4):584-93.

Dvorak J, Panjabi M, Gerber M, Wichmann W; CT-functional diagnostics of the rotatory instability of upper cervical spine: An experimental study on cadavers. Spine. April 1987;12(3):197-205.

Krakenes J, Kaale BR, Moen G, Nordli H, Gilhus NE, Rorvik J. MRI assessment of the alar ligaments in the late stage of whiplash injury:

A study of structural abnormalities and observer agreement; Neuroradiology 2002 Jul;44(7):617-24.

Kaale BR, Krakenes J, Albreksten G, Wester K; Whiplash-Associated Disorders Impairment Rating: Neck Disability Index Score According to Severity of MRI Findings of Ligaments and Membranes in the Upper Cervical Spine Journal of Neurortrauma; Volume 22, Number 4, April 2005, pp. 466–475.

Kaale BR, Krakenes J, Albreksen G, Wester K; Head Position and Impact Direction in Whiplash Injuries: Associations with MRI-Verified Lesions of Ligaments and Membranes in the Upper Cervical Spine; Journal of Neurotrauma; Volume 22, Number 11, November 2005, pp. 1294–1302.

Krakenes J, Kaale BR; Magnetic Resonance Imaging Assessment of Craniovertebral Ligaments and Membranes After Whiplash Trauma; Spine;

November 15, 2006, Volume 31, Number 24, pp 2820-2826.

Lindgren KA, Kettunen JA, Paatelma M, Mikkonen RH. Dynamic kine magnetic resonance imaging in whiplash patients; Pain Research and Management; Nov-Dec 2009;Vol. 14, No. 6; pp. 427-32.